Dame Jane Glover, one of today’s foremost authorities Handel’s music, shares what makes Xerxes one of his most popular operas: spectacular singing, drama, love stories and comedy. Composed hundreds of years ago, Xerxes is a perfect triangle of words, music, and visuals that still speaks to audiences today.

I am a bit of a Handel specialist; I’ve written a book about him as well as conducted a huge amount of his music. But I have never done Xerxes! I can’t believe I have gotten to my great age without doing it because, in a way, it’s one of the most popular of all his operas. I have conducted many of Handel’s serious works, but this one is very different, so I’m really excited to be here in Detroit!

Interestingly, Xerxes didn’t go over well in Handel’s lifetime. He was a man of the theater, which is why—with lots of short arias—it’s almost like a musical, with very few da capo arias. But the drama bowls along very quickly, and people genuinely have conversations. They don’t just sing “I’m so in love” or “I’m so angry,” but the drama moves along like a play. Unlike the opera seria that was popular when Handel wrote the work—characterized by immense arias and quick recitatives—Xerxes is much closer to the theater.

There are three sides to opera: words, music, and visuals. When it’s a perfect triangle, it’s a perfect art form. This all started with Francesco Cavalli’s and Claudio Monteverdi’s earliest operas, yet throughout the history of opera one of those sides pulls ahead. In the 18th century, it was all about the singing, all about the ornamentation, and less about the drama. Nicolò Minato, who wrote the libretto for Cavalli’s Xerxes in 1655, was the first to notice that the form was pulling away from that essential triangle.

Opera in Handel’s day was more also about visual and sonic spectacle, and sometimes that stops people from listening to the music or following the story. Yet Xerxes is so alive, due in great part to Handel’s mastery of words, music, and visuals. And still today, I think as practitioners, whether creators or interpreters, we’re always looking for that balance.

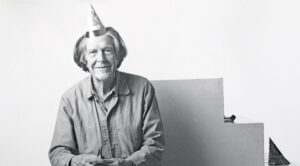

Dame Jane Glover with Detroit Opera Orchestra in rehearsal.

Austin Richey / Detroit Opera

At some point every character is allowed to be sympathetic. The goodies aren’t completely good. The baddies aren’t completely bad. The funnies aren’t completely funny. There’s quite a lot of humanity in this piece—not just in the libretto, but also Handel. Great heart, that man.

I think Xerxes almost misleads people’s understanding of opera. “Ombra mai fu” is almost a joke on Handel’s part: he opens this opera with a king singing an aria—to a tree! You must think it’s some sort of love song, but no, he’s singing because he likes the shade of its leaves. And that is the first jolt of many. Handel is telling a story here about somebody, but he's maybe not the somebody you think he is.

It's quite a tough story of brotherly rivalry for the love of a woman. Add in a woman in disguise who loves one of the brothers. And then all sorts of tangled webs are woven through deception. And throughout, Handel refines the drama with Elviro, a comic character who has these moments between the anxieties and the tensions between the main characters—it’s a work of genius.

Dame Jane Glover with Detroit Opera Orchestra in rehearsal.

Austin Richey / Detroit Opera

Handel being Handel, there are some wonderful opportunities for great singing! But it is the drama that drives the opera itself. It’s quite a subtle thing, but that’s what makes Xerxes so fascinating. And now it’s one of his most popular operas because it speaks to audiences, no question. It’s theatrical and vibrant, it’s got wonderful love stories, great heart, and wonderful comedy—what more do you want from an opera?