Lisa Montes Ph.D.

Department of Romance Languages and Literatures

University of Michigan

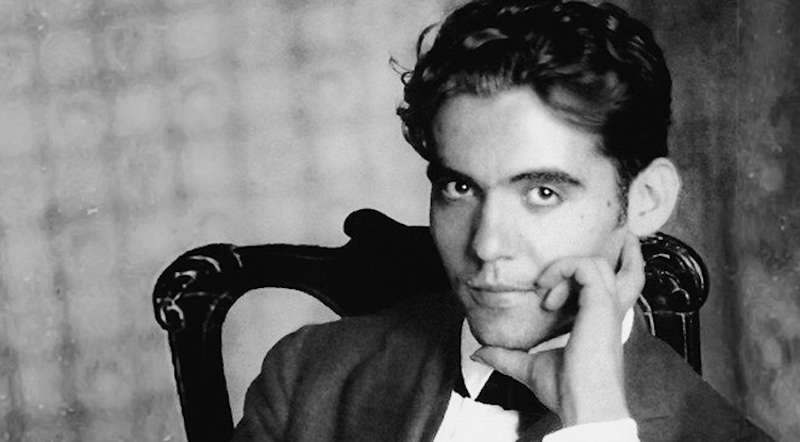

Born June 5,1898, in Fuente Vaqueros, a small town in Granada, Federico García Lorca spent much of his childhood experiencing the culture of rural Spain. The eldest of four, Lorca was the child of a teacher and wealthy landowner. From an early age, he had expressed an interest in the arts, and was considered an extraordinary pianist before discovering his literary talents. The images of nature and social conditions of his youth in rural Andalusia would greatly influence his writing in later years. His interactions with the gitanos, or Spanish Roma, however, would prove one of the greatest inspirations for some of his most revered works.

When the gitanos first arrived in Spain in the early 15th century, they enjoyed a peaceful coexistence with the country’s other inhabitants. As a result of their expulsion and persecution during the reign of the Reyes Católicos, this minority group has endured years of discrimination, giving rise to the various stereotypes that portray them in a harsh negative light. Once admired for their charisma, artistic ability and craftsmanship, the nomadic people were later regarded as beggars and thieves. In his compilations of poetry, Cante del poema jondo and Romancero gitano, however, Lorca portrays the Andalusian gitanos in a flattering manner, seeking to dispel the preexisting myths and stereotypes that represented them as nefarious and thieving. He admired the gitanos for their refusal to conform to the expectations of Spanish authority; as Lorca, too, questioned the rigid limits imposed by those in power. He sympathized with them, as one who had also suffered persecution by the conservative government for living outside of the margins of societal expectations. Due to his efforts to break down cultural and class barriers, Lorca is still revered by gitanos and payos (Spanish non-Roma) alike (Montes 105).

In 1919, Lorca relocated to Madrid where he spent several years living in the Residencia de Estudiantes, a residence hall that was considered the cultural center of Spain. Here he met famed icons such as artist Salvador Dalí and director Luis Buñuel. Lectures at the Residencia included distinguished guests like Marie Curie, Albert Einstein and Juan Ramón Jimenez. The Residencia was a forum for open discussion of intellectual ideas by some of the greatest minds of the 20th century. Free thought was encouraged and revered. Years later, the famed Generación del ‘27 was formed, which consisted of a group of writers, of varying styles and genres, collaborating out of desire to connect Spanish popular folklore and classical literary styles with the avant-garde. While originally created to bridge this cultural gap in poetry, the Generación del ’27 would soon grow to include intellectuals of various disciplines. Among these were surrealist painter Óscar Dominguez, caricaturist K-Hito and sculptor Maruja Mallo. This community of enlightened individuals thrived until the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936. Under the hash right-wing dictatorship, censorship increased, scientific advances were halted, and many artists, writers and thinkers were exiled from Spain.

In 1919, Lorca relocated to Madrid where he spent several years living in the Residencia de Estudiantes, a residence hall that was considered the cultural center of Spain. Here he met famed icons such as artist Salvador Dalí and director Luis Buñuel. Lectures at the Residencia included distinguished guests like Marie Curie, Albert Einstein and Juan Ramón Jimenez. The Residencia was a forum for open discussion of intellectual ideas by some of the greatest minds of the 20th century. Free thought was encouraged and revered. Years later, the famed Generación del ‘27 was formed, which consisted of a group of writers, of varying styles and genres, collaborating out of desire to connect Spanish popular folklore and classical literary styles with the avant-garde. While originally created to bridge this cultural gap in poetry, the Generación del ’27 would soon grow to include intellectuals of various disciplines. Among these were surrealist painter Óscar Dominguez, caricaturist K-Hito and sculptor Maruja Mallo. This community of enlightened individuals thrived until the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936. Under the hash right-wing dictatorship, censorship increased, scientific advances were halted, and many artists, writers and thinkers were exiled from Spain.

In 1929, while still in Spain, Lorca was undergoing an emotional crisis, fearing he had peaked in creativity and popularity. This prompted his search for new experiences and inspiration. Additionally, he was struggling with some of his closest relationships. Lorca had fallen into a deep depression following a falling out with his close companion, sculptor Emilio Aladrén. Soon after the rupture of this relationship, the young writer experienced a profound betrayal by two of his dearest friends, Dalí and Buñuel, upon the release of their project Un chien Andalou (An Andalusian Dog), a short surrealist film which Lorca claimed had been created to mock him. While never confirmed, Lorca perceived the movie as a direct allusion to his naivety and fear of breaking from his traditional upbringing. Although there were existing problems in his friendship with the artist and director, the production of this film was the final blow to the relationship. In addition to the personal struggles endured, Lorca felt highly overwhelmed by the political situation in Spain. He had grown increasingly skeptical of the dictatorship of Miguel Primo de Rivera, and desired to see change. It was at this point that the poet solidified his decision to temporarily leave his native country.

In June of 1929 Lorca embarked on his journey to North America where he was scheduled to lecture in both New York and Cuba. Upon arriving in New York, Lorca was quickly excited by the chaos of the busy streets and awed by the enormity of the skyscrapers, an attitude that would drastically change after a few short weeks. This fascination with the city began to dissipate after having visited a nightclub in Harlem known as Small’s Paradise, a bar frequented by the borough’s African American population. Here Lorca witnessed the poverty and marginalization of the minority group. He identified with what he understood as their desire to exist freely, much like the gitanos, and himself, as he often felt marginalized by the conservative constraints of twentieth century Spain. Contrasting the discrimination facing the African American population of Harlem with the widespread wealth he had encountered in other areas of the city, Lorca became disenchanted with New York. The skyscrapers that had once fascinated him began to symbolize the mechanization of society as they blocked out the sunlight and disrupted the flow of the nature he so cherished. He now viewed the city as cold, harsh and dehumanizing with materialism at its heart. For Lorca, New York represented the struggle of man to balance the sickness that had invaded his body and soul, and he desperately longed to return to his native Andalusian soil (Montes 177).

In his book Federico García Lorca and the Culture of Male Homosexuality, Ángel Suhuquillo examines the position of Spanish culture on homosexuality and its effect on the works of canonical writers and artists. Suhuquillo claims that, due to the rampant homophobia of early twentieth century Spanish society, the contributions of Lorca and other homosexual artists were ill received, with traces of this institutionalized bigotry even lasting today among modern day critics. In 2009, renowned Lorca historian, Ian Gibson, published Lorca y el mundo gay, a biography detailing the poet’s life and the lovers with whom he related. Because some considered his writing intensely homoerotic, much of Lorca’s literature had been banned in 1954 and still censored until 1975, the year marking the death of fascist leader Francisco Franco. The poet’s suspected homosexuality was a subject considered taboo and rarely spoken of, even by the members of Lorca’s family. It was not until the 1980s that his alleged homosexuality became acknowledged, which Gibson blames on the deeply rooted homophobia that permeated Spanish society. After rereading Lorca’s early poems, Gibson states, "I discovered an anguished, tortured, gay love ... Those who deny his homosexuality must now shut up, or at least question their prejudices. It's a relief after so many decades of obfuscation and silence, to reveal the truth."

One of the most influential people in Lorca’s life was stage actress and political activist Margarita Xirgu. After meeting the young writer in a Madrid bar in 1926, the actress accepted the invitation to stage Lorca’s production of Mariana Pineda which would premiere the following summer in Barcelona, with Salvador Dalí designing the wardrobe. The great success of the production marked the beginning of a long-lasting friendship and creative partnership between the writer and the actress. As fascist political tensions arose during the regime of General Francisco Franco, the outspoken actress posed a major threat to the far-right dictatorship, often referred to as Margarita la Roja (Margarita the Red), for her openly left-leaning Communist views. For this reason and the fact that she was a lesbian, Lorca’s companion knew it would not be safe to stay in Spain, and therefore, exiled to South America where she remained until her death in 1969. Fearing her friend would meet an untimely demise were he to continue living in Spain, Margarita urged Lorca to relocate with her. At the time, however, he was completing his final work, La casa de Bernarda Alba, and had decided to remain in his native land until the play was complete. He did, however, plan to reunite with her shortly after. Sadly, before this could happen, Lorca was dragged by soldiers to a field and executed.

Lorca and his literature have been studied and analyzed by many literary scholars. Although the topics are numerous and varied, some of the more prevalent studies discuss his alleged homosexuality, the prevailing sense of tragic determinism in his productions and the symbolism and role of nature in his literature. As one of Spain’s most prolific and revered writers, Federico García Lorca causes his readers to go beyond the text and make connections that help to better understand the human condition, transcending cultural and social boundaries. Despite previous attempts to silence his voice, the memory and messages of Federico García Lorca live on in his native land and beyond.

Works Consulted

Gibson, Ian. Lorca y el mundo gay: "Caballo azul de mi locura". Barcelona: Editorial Planeta, 2009. Web.

Montes, Lisa. Sociological Approaches to García Lorca’s Literary Productions. Madrid: Ediciones del orto, 2016. Print.

Suhuquillo, Angel. Federico García Lorca and the Culture of Male Homosexuality. North Carolina: McFarland and, 2007. Print.