Opera has always been about grand emotions—love, betrayal, joy, despair—but sometimes those stories are best told in smaller, sharper doses. That’s where the tradition of the double bill comes in: two short operas presented together in a single evening, creating a powerful balance of contrast and connection.

By Austin T. Richey, Ph. D.

Digital Media Manager and Storyteller, Detroit Opera

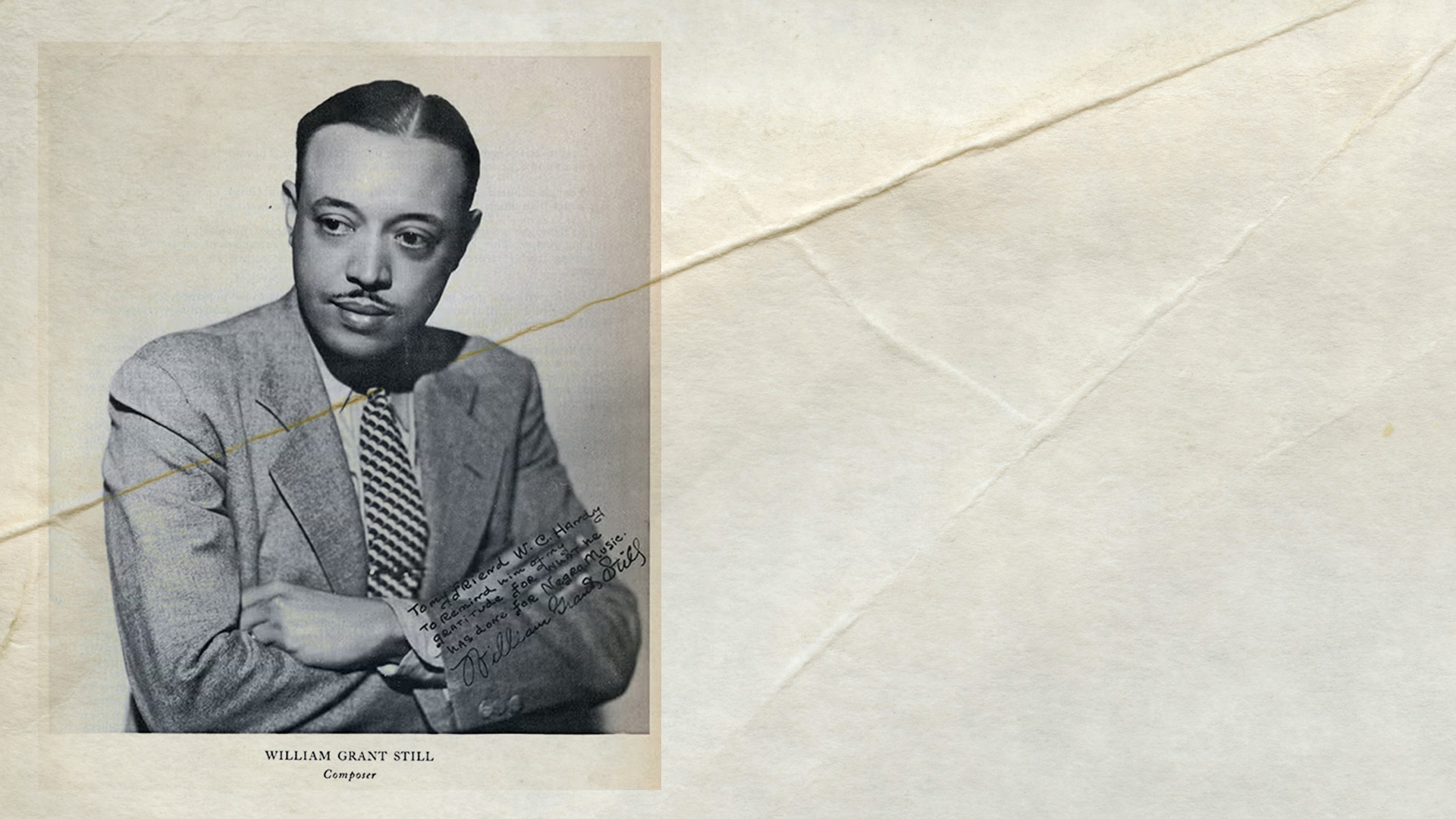

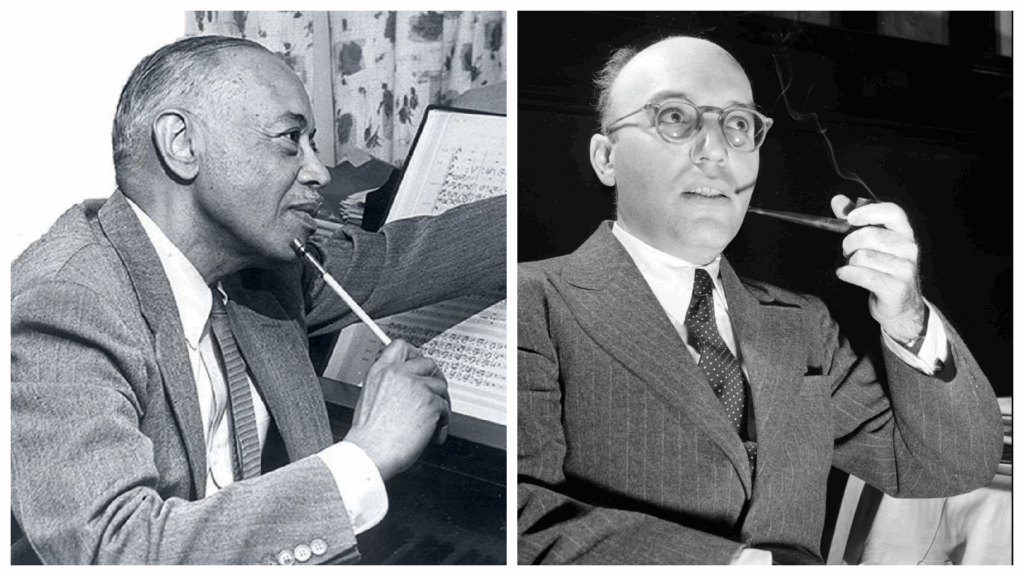

This season, Detroit Opera brings audiences a rare double bill of American one-act operas: William Grant Still’s Highway 1, USA (1941) and Kurt Weill’s Down in the Valley (1948). Together, these works shine a spotlight on 20th-century composers who wove opera into the fabric of American life, rooting high art in everyday experience, jazz harmonies, and folk traditions.

The History of Opera Double Bills

The pairing of two operas into a single evening is more than a matter of convenience—it is a creative strategy, a theatrical gesture of contrast, counterpoint, and resonance. The most popular operatic pairing is Pietro Mascagni’s Cavalleria rusticana and Ruggero Leoncavallo’s Pagliacci.

Though written independently in the 1890s, opera houses began staging them together in the early 20th century, finding that their themes of jealousy, betrayal, and violence complemented one another perfectly. Over time, “Cav/Pag” became a staple of the repertoire—a kind of operatic shorthand for intensity. Consider, too, how the pairing has been propelled by two of opera’s most iconic musical moments: the soaring Intermezzo from Cavalleria rusticana and the heart-rending tenor aria “Ridi, Pagliaccio” from Pagliacci. These excerpts became popular as standalone recordings, solidifying the double bill’s cultural footprint far beyond the opera house.

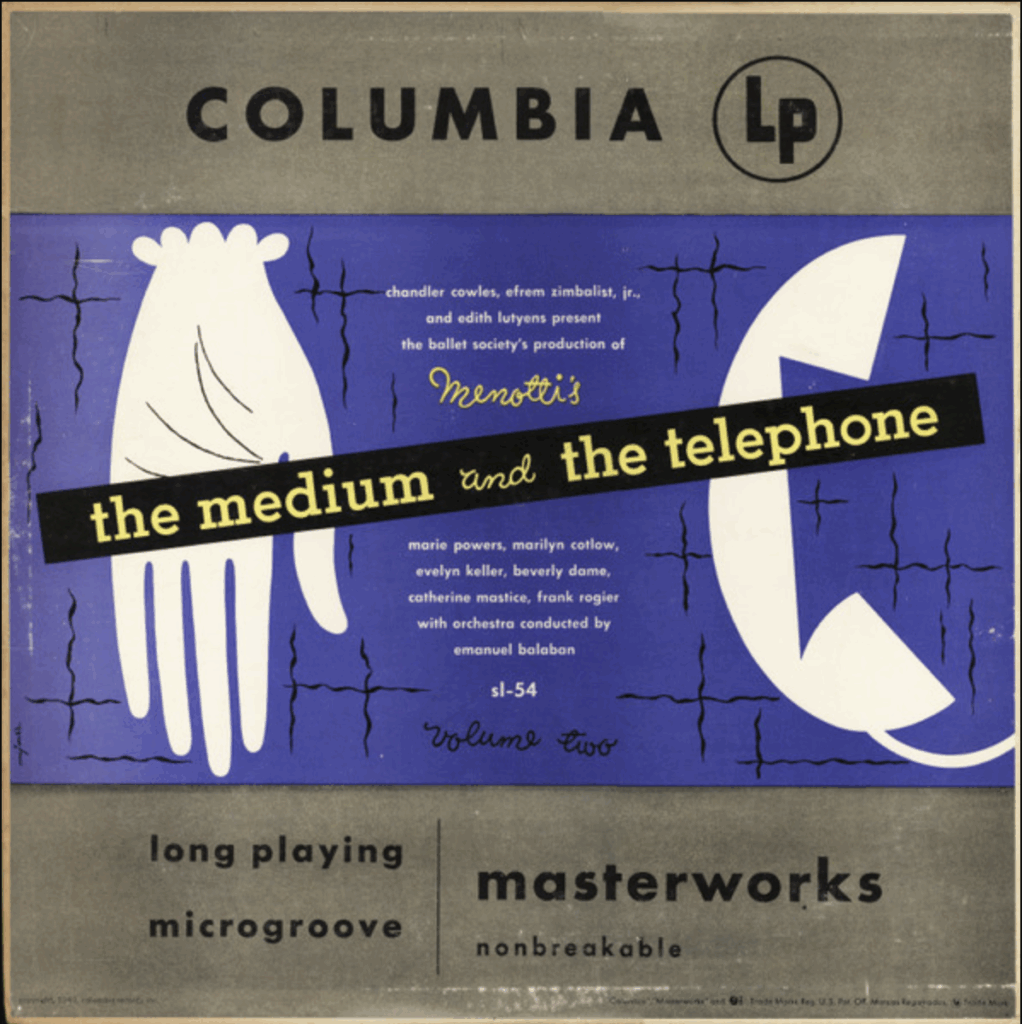

Gian Carlo Menotti premiered his two short works The Telephone and The Medium (1947) himself as a pair on Broadway. The Telephone is a comic chamber opera about a young man competing with the telephone for his girlfriend’s attention, while The Medium is a gothic tale of a fraudulent fortune-teller haunted by the supernatural. Together they show Menotti’s range, from lighthearted satire to chilling drama.

Maurice Ravel’s L’heure espagnole (1907) is a witty, clockwork comedy filled with rhythmic sparkle and farcical timing. It’s often paired with Francis Poulenc’s La voix humaine (1958), a one-woman psychological drama told entirely through a phone call. Together, the two create a striking balance: Ravel’s bustling comic ensemble sets the stage for Poulenc’s raw emotional monologue. The pairing underscores how opera can pivot from slapstick to searing confession within a single evening.

The most famous multi-opera evening, Giacomo Puccini’s Il Trittico (1918), brings together three one-act operas that couldn’t be more different:

- Il tabarro – a shadowy, verismo thriller set on the Seine

- Suor Angelica – a lyrical, spiritual tragedy

- Gianni Schicchi – a brilliant comedic romp and Puccini’s only full-length comedy

Originally intended to be performed as a complete trilogy, Il Trittico demonstrates the dramatic power of contrast: murder, redemption, and mischief packed into one evening. While companies sometimes present the operas individually, the full triple bill remains one of opera’s most satisfying journeys across tone and genre.

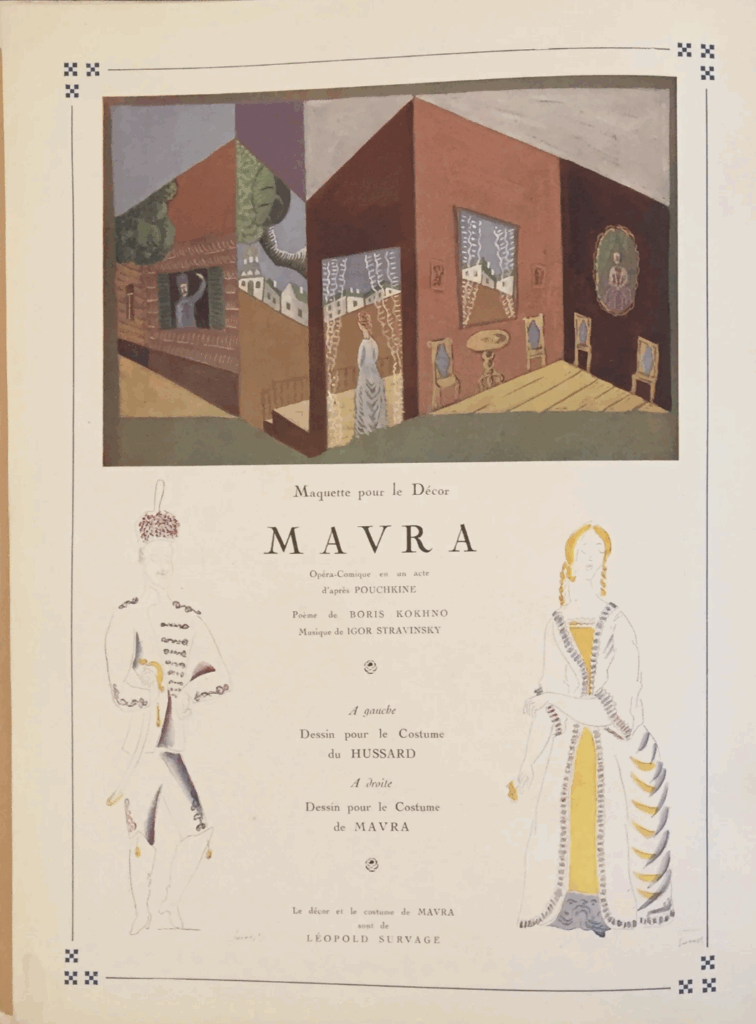

Igor Stravinsky’s Mavra (1922) is another one-act that frequently appears in double or triple bills. Rarely staged on its own, Mavra’s neoclassical sharpness and compact scale make it an ideal companion piece—often paired with other short Stravinsky works such as The Nightingale (1914) or The Flood (1962). Across these brief operas, Stravinsky’s gift for tightly constructed drama and jewel-box orchestration makes them especially effective in multi-opera evenings, where their concentrated brilliance can shine alongside contrasting styles and eras.

The double-bill structure offers several artistic advantages, especially the variety in tone and scale. A light, comic piece can contrast with a serious or tragic work; an intimate chamber score can be balanced by a more expansive orchestration. But this approach also allows thematic or formal dialogue. Works may echo each other in theme (e.g. family, sacrifice, identity) or through musical gestures (e.g. shared intervallic language, parallel dramatic arcs). From a practical standpoint, short operas often are underperformed due to their modest scale, so pairing them allows companies to mount adventurous programs without the full risk or cost of a grand opera.

Above all, a double bill invites the audience into a conversation—seeing one story through the lens of another, comparing resonances, and encouraging reflection.

Highway 1, USA

Still’s Highway 1, USA tells the story of a hardworking couple sacrificing everything for a younger brother’s education, only to find their generosity repaid with selfishness and betrayal. It’s a deeply American tale, framed by blues-tinged harmonies and gospel-inflected vocal lines. Highway 1, USA began life in 1941 under the title A Southern Interlude, with text by Verna Arvey; Still continued revising it, before finalizing it in the early 1960s. The work is in one act divided into two scenes. Its premiere came relatively late—on May 11, 1963—at Coral Gables High School during the University of Miami’s Festival of American Music.

Musically, Highway 1, USA is lean but emotionally potent. Still marries lyrical vocal writing with orchestration that balances Romantic sweep and vernacular inflection (blues, gospel, hymn textures). The harmonic language is enriched by “blue notes,” modal shifts, and occasional chromaticism that suggests but does not overburden the drama. The rhythms are grounded in regular pulse, but the phrasing and syncopations subtly evoke jazz sensibilities.

Dramatically, the opera has the feel of social realism: Bob and Mary run a gas station while supporting Bob’s younger brother Nate through college in fulfillment of their late mother’s dying wish. Over time, Nate becomes idle and resentful; ultimately, in a crisis, he stabs Mary when she rejects him. Mary survives, Nate confesses, and Bob and Mary sing of a hopeful future. The chorus plays a Greek chorus-like role, commenting on the action, shifting loyalties, and offering communal voice. Highway 1, USA has often been overlooked; its recent revivals (for example, at LA Opera and Opera Theatre of St. Louis) are helping to restore its place in American operatic repertory.

Down in the Valley

Weill’s Down in the Valley (1948) draws on Southern folk songs and spirituals to tell the tragic story of a man condemned for killing in defense of his lover’s honor. Originally designed for community performance, it bridges Broadway accessibility with operatic intensity. Down in the Valley is sometimes called a “folk opera” or “ballad opera” because of its integration of American folk melodies and spirituals. It was designed to be performable by community groups, with modest orchestration and a clear narrative.

Weill weaves in traditional songs such as “The Little Black Train,” “Hop Up, My Ladies,” and of course “Down in the Valley.” The score marries folk simplicity with subtle harmonic complexity: While the melodies may feel familiar, the orchestration and interludes often carry more dissonant or chromatic colorings underneath. The plot is tragically simple: a love triangle leads to a fatal confrontation.

In some versions, Brack kills his rival (Bouché) defending Jennie; Brack is captured, tried, and ultimately executed, and Jennie laments his death. The narrative draws on the traditions of Southern ballad tragedy, spiritual longing, and moral consequence. In other versions, however, the outcome differs—some ballad variants end with reconciliation, others with escape, and still others leave the final moral unresolved.

Importantly, the opera’s libretto does not specify which ending must occur, leaving the resolution open to interpretation. This flexibility gives directors significant latitude: they may choose the harsher, more tragic conclusion; a more ambiguous parting; or a version that reflects the particular emotional or political lens of a given production.

Why They Work Together

When presented together, Highway 1, USA and Down in the Valley illuminate the diversity of American musical expression. First, the pairing highlights two distinct yet intersecting threads of American vernacular music. Highway 1, USA draws deeply from blues and gospel traditions, rooted in the African American experience and the rhythms of mid-century realism. In contrast, Down in the Valley is steeped in Southern folk melodies, spirituals, and the communal ballad tradition. Heard side by side, these operas trace parallel paths through America’s soundscape—each revealing how everyday musical forms became vessels for storytelling and emotional truth.

Their shared dramatic scale also creates a compelling rhythm for the evening. Both works are concise, one-act operas, yet each delivers a complete emotional arc. Audiences move from the intimate domestic drama of Still’s Highway 1, USA into the archetypal folk tragedy of Weill’s Down in the Valley. The contrast in pacing and tone heightens the impact of both pieces, amplifying their emotional stakes and the universality of their themes.

At their core, both operas grapple with questions of morality, love, sacrifice, and betrayal. They examine the fragile balance between personal aspiration and social responsibility—how dreams, duty, and love collide in the American imagination. These stories, though set in different worlds, converge in their insistence on empathy and the cost of idealism.

Finally, the two works complement one another in practical and artistic terms. With modest orchestration and small casts, they lend themselves naturally to a double bill, allowing for flexible staging and close collaboration among singers and musicians. The result is an evening that is both economical and deeply affecting—two mirrors held up to America’s soul, reflecting its complexities in song.

Why Double Bills Matter Now

In presenting Highway 1, USA and Down in the Valley together, Detroit Opera offers a vision for what American opera can be today. This double bill is both homage and innovation: a dialogue between vernacular roots and modern expression, between community storytelling and artistic experimentation.

At its heart, the pairing amplifies the diversity of American opera. Both works emerge from traditions outside the European mainstream, composed by artists who drew inspiration from the musical languages of everyday life. William Grant Still’s rarely performed Highway 1, USA channels blues, gospel, and the emotional cadences of African American experience, while Kurt Weill’s Down in the Valley reimagines folk and spiritual traditions through the lens of communal myth. By programming these operas together, Detroit Opera spotlights composers who expanded the definition of what opera could sound like, and whose work resonates with the pluralism of American identity.

With this pairing, audiences are invited to listen across genres and idioms, to hear how two composers navigate form, tone, and texture within contrasting sound worlds. The shift from Still’s midcentury realism to Weill’s folk modernism illuminates how American composers have long negotiated between classical form and popular vernacular, between the concert hall and the front porch.

Dramatically, the evening offers a layered emotional arc. Highway 1, USA begins with intimate domestic tragedy, while Down in the Valley moves toward an archetypal, almost mythical resolution. The result is a program that evolves in tone and perspective, inviting reflection on the shared moral terrain—love, sacrifice, betrayal—that underlies both stories.

Practically and philosophically, one-act operas also serve as a bridge to broader audiences. Their compact scale and emotional immediacy make them accessible entry points for those new to opera, while still offering depth and richness for seasoned listeners. Together, they expand the repertoire and open the stage to new ways of experiencing the art form.

In Detroit, this double bill feels particularly resonant. Here, where jazz, gospel, Motown, and techno coexist as living traditions, staging operas rooted in American vernacular idioms opens a dialogue with the city itself. The double-bill format does more than double the music—it doubles the meaning. It allows audiences to experience American opera in stereo: two frequencies, two visions, harmonizing and diverging in turn. In doing so, it invites us to listen more closely—not just to the stories onstage, but to the sound of who we are.

Highways and Valleys: Two American Love Stories will be presented at the Detroit Opera House December 7–13, 2025.