Handel’s London: A City in Opera

by Austin Richey, Ph.D.

Digital Media Manager and Storyteller, Detroit Opera

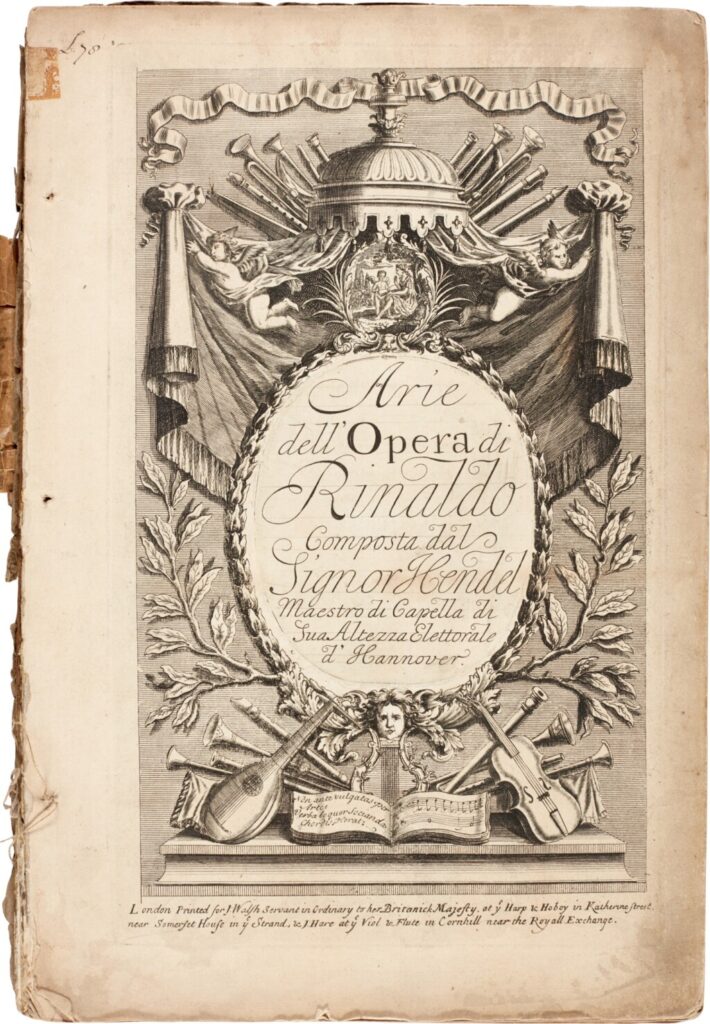

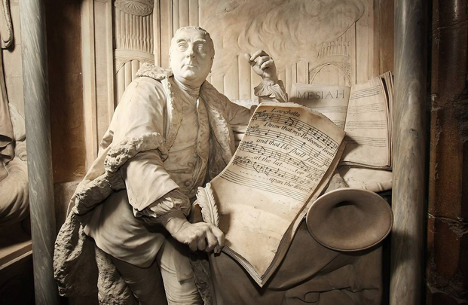

In the early 18th century, London was a city of spectacle. Theaters buzzed with energy, coffeehouses teemed with debate, and the newly formed Royal Academy of Music sought to establish Italian opera as the pinnacle of entertainment for the city’s elite. Into this world stepped a 25-year-old German composer named George Frideric Handel, who, in 1711, stunned London audiences with his first Italian opera for the English stage: Rinaldo.

Rinaldo and the Italian Opera Craze

Premiering at the Queen’s Theatre in the Haymarket on February 24, 1711, Rinaldo was London’s first opera composed entirely in Italian. It was a calculated gamble. While Italian opera had gained traction in the city, no composer had yet dared to present a fully-fledged work in the style. Handel, backed by impresario/poet Aaron Hill, saw an opportunity to dazzle.

And dazzle it did. With its thrilling plot—drawn from Torquato Tasso’s epic poem Gerusalemme Liberata —and an arsenal of musical fireworks, Rinaldo was designed to impress. Hill and Handel leveraged every available theatrical trick: real birds were released on stage, elaborate battle scenes unfolded with incredible stage machinery, and the production embraced London’s hunger for spectacle. The music, too, was a revelation. The hauntingly beautiful aria “Lascia ch’io pianga” would go on to become one of Handel’s most famous melodies, while the bravura writing for the castrato Nicolò Grimaldi (known as “Nicolini”) solidified his status as an operatic superstar.

A Premiere of Spectacle: Theatrical Magic and Extra-Musical Sounds

London audiences had never seen anything quite like Rinaldo. The Queen’s Theatre, equipped with the latest stage technology, became a playground for dramatic innovation. One of the most talked-about elements of the production was the use of real birds. During the aria “Augelletti, che cantate, (Little birds that are singing),” sung by Almirena, trained songbirds were released into the theater, their chirping blending with the delicate continuo accompaniment. This use of extra-musical sound—natural birdsong within an opera—created an effect that reportedly was both enchanting and chaotic, as some birds refused to cooperate, flying into the audience instead of remaining on stage.

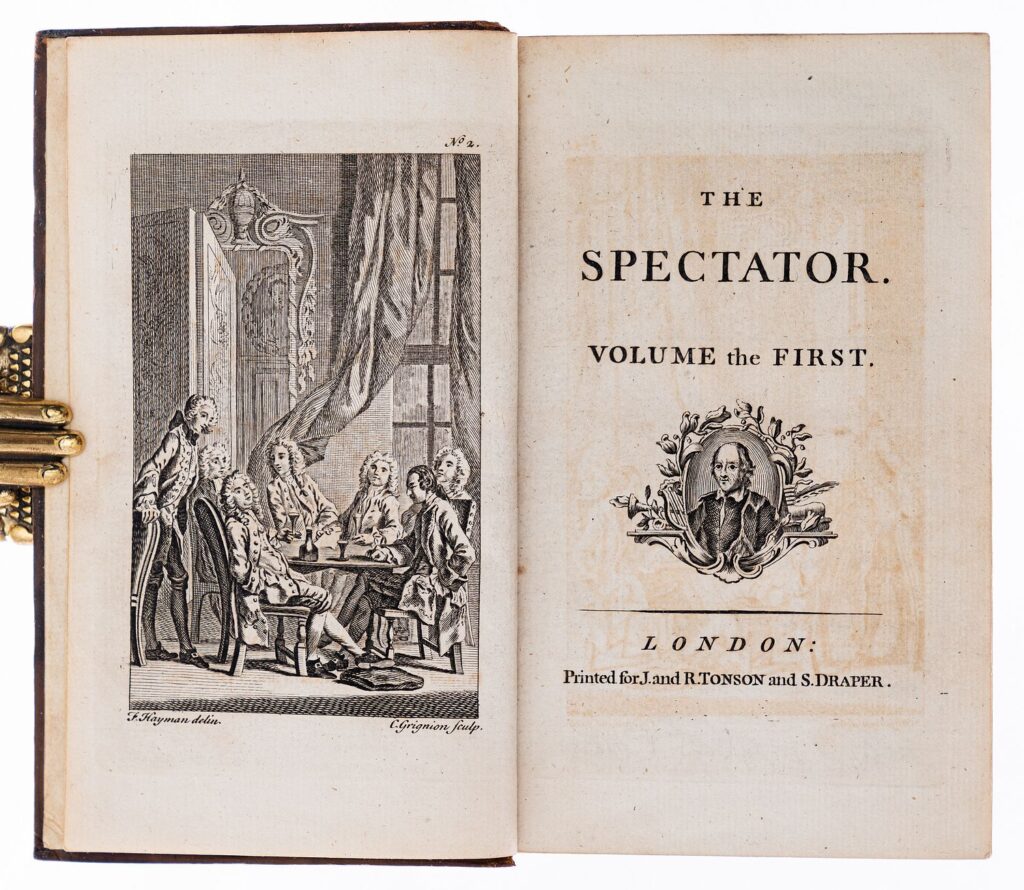

As Handel’s contemporary Richard Steele wrote in the satirical journal The Spectator,

As I was walking in the streets about a fortnight ago, I saw an ordinary fellow carrying a cage full of little birds. He had been buying sparrows for the opera, he said. Sparrows for the opera? asked his friend, licking his lips. What, are they to be roasted? No, no, says the other, they are to enter toward the end of the first act, and to fly about the stage.

This strange dialogue awakened my curiosity so far that I immediately bought the opera, by which means I perceived the sparrows were to act the part of singing birds in a delightful grove; though, upon a nearer inquiry, I found that they flew in sight while the music proceeded from a consort of flageolets and birdcalls planted behind the scenes.

There have been so many flights of them let loose in this opera that it is feared the house will never get rid of them…they make their entrance in very wrong and improper scenes, so as to be seen flying in a lady’s bedchamber, or perching upon a king’s throne; besides the inconveniences which the heads of the audience may sometimes suffer from them.

– (Richard Steele and John Addison, “House Rules: Sparrows take over the opera,” The Spectator, 1711).

Beyond the birds, Rinaldo featured spectacular battle scenes between Christian and Saracen forces, complete with onstage cavalry charges and elaborate pyrotechnics. Inspired by recent advences in stage mechanics, Nicolini, as Rinaldo, was lifted into the air using a stage harness to simulate flight. The image of the heroic knight soaring above the battlefield was a breathtaking spectacle that solidified the production’s reputation as the most visually ambitious opera London had seen. Another key moment involved Rinaldo’s enemy, the sorceress Armida, summoning infernal spirits amidst rolling thunder and flashes of fire—created through ingenious use of lighting effects and offstage percussion. London theatergoers, accustomed to Shakespearean drama and masques, were enthralled by the immersive nature of these operatic illusions.

A City in Transition

Handel’s London in 1711 was a city of contradictions. On one hand, it was experiencing a cultural golden age—art, literature, and music flourished, driven by a wealthy aristocracy eager to patronize the arts. On the other, it was a place of political instability. Queen Anne was on the throne, but the question of succession loomed large. The city’s social fabric was shaped by rapid expansion, a growing middle class, and an increasingly international character, making it a prime breeding ground for new artistic ideas.

Opera was more than just entertainment; it was a statement of cultural aspiration. For the British elite, embracing Italian opera signified sophistication, aligning them with the grandeur of European courts. For Handel, it was an opportunity. The success of Rinaldo ensured his place in London’s musical world, setting the stage for a career that would see him become one of the defining figures of English music.

The Legacy of Rinaldo

Rinaldo was an immediate triumph, receiving multiple revivals over the next few years. Its success cemented Handel’s reputation, paving the way for his later operatic and oratorio masterpieces. More important, it signaled London’s emergence as a major center for Italian opera, a genre that would dominate its theaters for decades. Though the Queen’s Theatre (later the King’s Theatre and eventually His Majesty’s Theatre) no longer stands in its original form, the legacy of Rinaldo lives on. It was the opera that announced Handel to London, the city he would call home for the rest of his life. From that moment in 1711, the young German composer became, in spirit and in sound, thoroughly English.

Handel’s Rinaldo is at Detroit Opera February 22 – March 22, 2025

BUY TICKETS