The Mechanics of Baroque Opera: Illusion, Engineering, and Spectacle

by Austin Richey, Ph.D.

Digital Media Manager and Storyteller, Detroit Opera

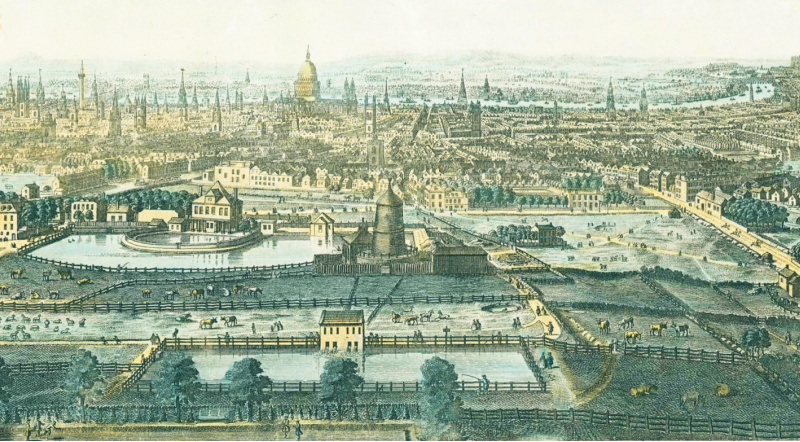

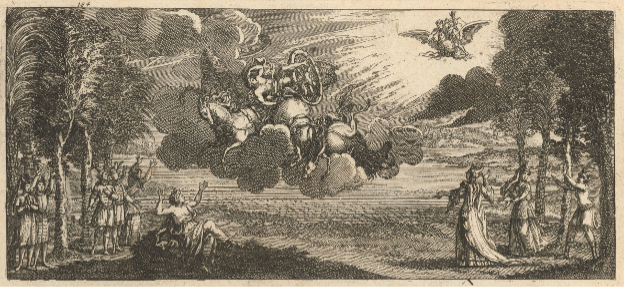

Opera in the Baroque era was as much about visual splendor as it was about music. Audiences didn’t just come to hear exquisite arias—they came for stage magic, for floating castles, fiery infernos, and gods descending from the heavens. The theaters of Handel’s day were laboratories of illusion, where stage designers pushed the limits of technology to transport audiences to enchanted landscapes and mythic battles.

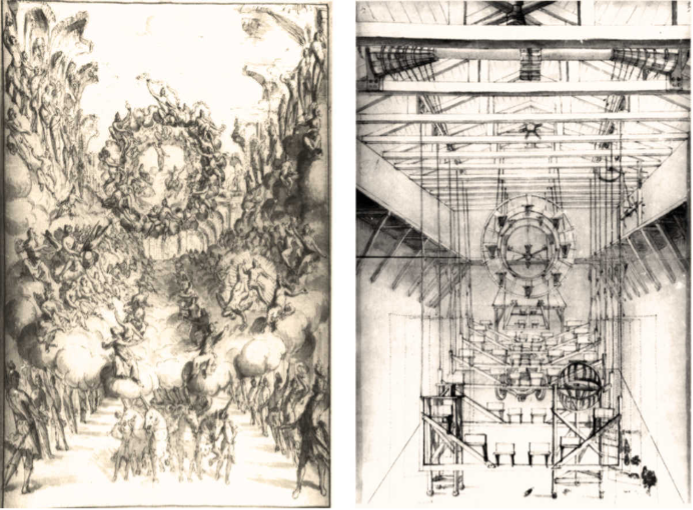

Behind the scenes, an intricate system of pulleys, winches, painted flats, and trapdoors allowed for stunning transformations. Whether it was Armida’s enchanted palace vanishing in an instant in Rinaldo or Neptune’s chariot rising from the sea in Jean-Philippe Rameau’s Dardanus, the mechanics of Baroque opera sets were feats of ingenuity—designed to amaze, bewilder, and dazzle the senses.

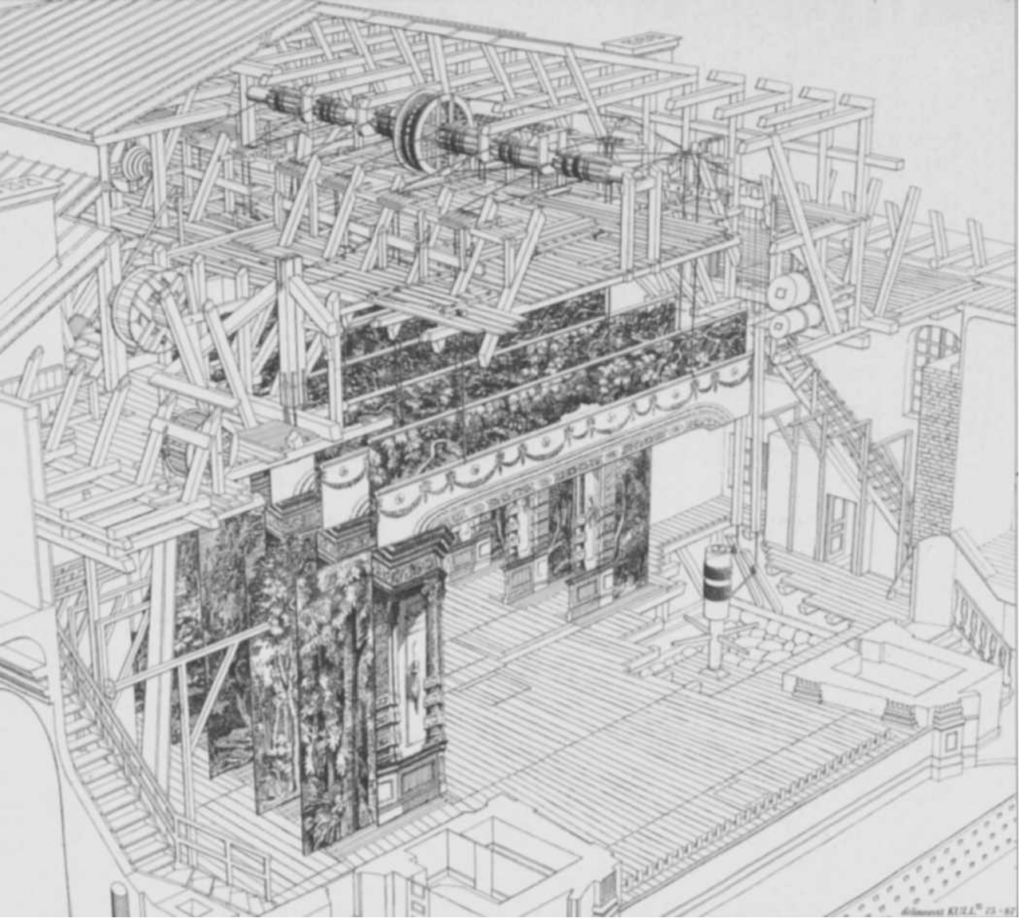

The Art of Transformation: The Wing and Groove System

At the heart of Baroque stagecraft was the wing and groove system, a technique perfected by Italian set designers and adopted across European theaters. Here’s how it worked: Painted scenic flats (or wings) were placed in vertical grooves on either side of the stage. These flats were arranged in layers, creating a forced-perspective illusion that made the st age seem far deeper than it was. When a scene needed to change, stagehands—often working in coordinated teams—slid entire sets sideways into the wings, revealing a new backdrop. This allowed for rapid, seamless transitions between scenes, often executed in full view of the audience to heighten the spectacle.

A production like Rinaldo would require multiple layered perspectives, giving the illusion of sweeping landscapes or grand palaces stretching into the distance. Combined with candlelit footlights and carefully painted shadows, these sets created an immersive visual experience long before the invention of modern lighting.

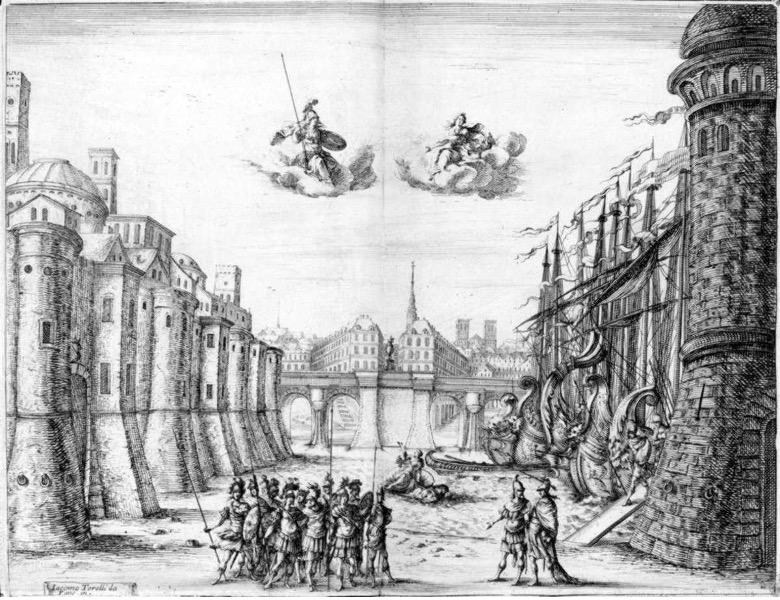

Flying Machines and Spectacle: Deus ex Machina

One of the most dramatic effects in Baroque opera was the deus ex machina—literally, “god from the machine.” This referred to the use of elaborate flying machines, allowing characters to descend from the heavens or be lifted into the sky.

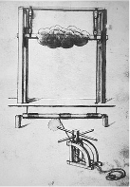

Right: a sketch of the construction employed.

Counterweighted pulley systems enabled gods and supernatural beings to be lowered gracefully onto the stage. Winches and rotating cranks, hidden above the stage, allowed figures like angels, witches, and spirits to hover mid-air. Theaters like the Queen’s Theatre in Haymarket (where Rinaldo premiered in 1711) were built with reinforced ceilings to accommodate these complex mechanisms.

During Rinaldo, audiences would have seen sorcerers flying on clouds, warriors soaring into battle, and enchanted spirits appearing out of thin air. Nicolò Grimaldi (Nicolini), the celebrated castrato playing Rinaldo, was famously hoisted into the sky using such a rig—creating an unforgettable heroic spectacle.

Storms, Fires, and Special Effects

Beyond flying machines, Baroque opera houses were filled with theatrical pyrotechnics to simulate storms, explosions, and divine interventions. Thunder effects were created using sheets of metal shaken offstage or cannonballs rolled down wooden troughs. Lightning was simulated with flashing mirrors, ignited gunpowder, or magnesium flashes while smoke and fog were achieved using burning resin or hidden steam devices.

During Rinaldo, when Armida summons her demonic legions, audiences would have seen billowing smoke, bursts of fire, and rolling thunder, all carefully timed to match the orchestral crescendos. These effects turned Baroque opera into a multi-sensory experience, where sight, sound, and even scent (from burning resins) combined to heighten drama.

Hidden Machinery: The Secrets Beneath the Stage

Many Baroque theaters contained hidden trapdoors and rotating platforms that enabled complex illusions, such as rising platforms that made objects or characters appear suddenly from below the stage or revolving set pieces that could transform a dark cave into a dazzling palace with a single turn. Hidden water tanks, in some cases, allowed for simulated fountains and even small-scale naval battles. This kind of engineering was particularly useful for operas with supernatural themes, such as Rinaldo, where entire enchanted landscapes needed to materialize and vanish in an instant.

The Grand Illusion: Making the Impossible Possible

For 18th- century audiences, opera wasn’t just a musical event—it was an extravaganza. The illusion of limitless space, the seamless changes between dreamlike worlds, and the spectacle of gods and warriors defying gravity helped make opera a social and artistic phenomenon.

Handel and his contemporaries composed with spectacle in mind. The dramatic flourishes in their scores—thundering orchestral passages, soaring arias—were designed to match the grandeur of the stage effects. The theater became a place where the impossible became possible, where an audience could watch a singer lifted into the heavens and, for a moment, believe it was real.

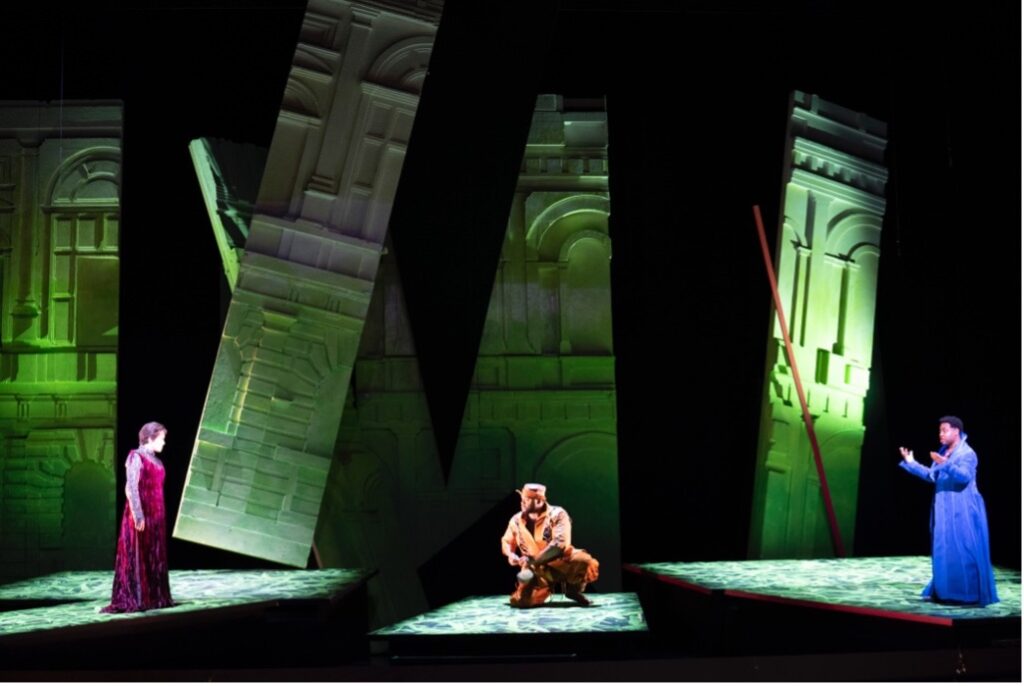

While modern productions rarely use the exact mechanics of the 18th century, their influence lingers. Contemporary stagings of Handel’s operas often incorporate bold visual storytelling, intricate projections, and flying rigs, echoing the spirit of Baroque spectacle. Directors continue to embrace the magic and illusion that defined the Baroque stage, proving that, even in the digital age, the technological wonders of Baroque opera set design still have the power to amaze and transport audiences—just as they did in Handel’s London.

Handel’s Rinaldo is at Detroit Opera February 22 – March 22, 2025

BUY TICKETS