Detroit: Love, Labor and the Robot Soul

In Detroit, machines have always had rhythm.

From the clang of assembly lines at Ford’s Rouge Plant to the deep thump of bass at an underground techno rave, the Motor City has spent a century dancing with automation. But what happens when the machines start dancing back? When robots don’t just build our cars—but write our music, whisper our names, and maybe even break our hearts?

In the early 20th century, Detroit gave the world the assembly line. By mid-century, it was ground zero for the industrial robot. By the 1980s, it created a new kind of music that fused mechanical precision with deep emotional urgency: techno.

In Detroit, the robot is more than a metaphor. It’s a legacy—of labor, control, loss, and survival. From the cold logic of automation to the warm pulse of the dance floor, Detroit’s history with machines is not just technical. It’s intimate.

Fordism and the Logic of the Line

In 1913, Henry Ford unveiled the moving assembly line at his Highland Park plant—a mechanical choreography that broke down car manufacturing into fixed, repetitive tasks. It slashed production times and gave rise to the mass market. A Model T that once took 12 hours to build could now be assembled in 90 minutes. It was hailed as genius. But the line had another name among workers: “the grind.”

The line turned labor into rhythm. Not the organic, improvisational rhythm of human work—but the enforced beat of the machine. Workers were bound to its tempo. It dictated their movements, breaks, posture—even their injuries. This mechanization of labor created something powerful and paradoxical: material prosperity through spiritual erosion. Detroit’s economic boom came hand-in-hand with alienation. And this alienation was racialized. During the Great Migration, Black workers from the South filled dangerous, low-paying jobs on the line—earning wages, but often at the cost of dignity and health.

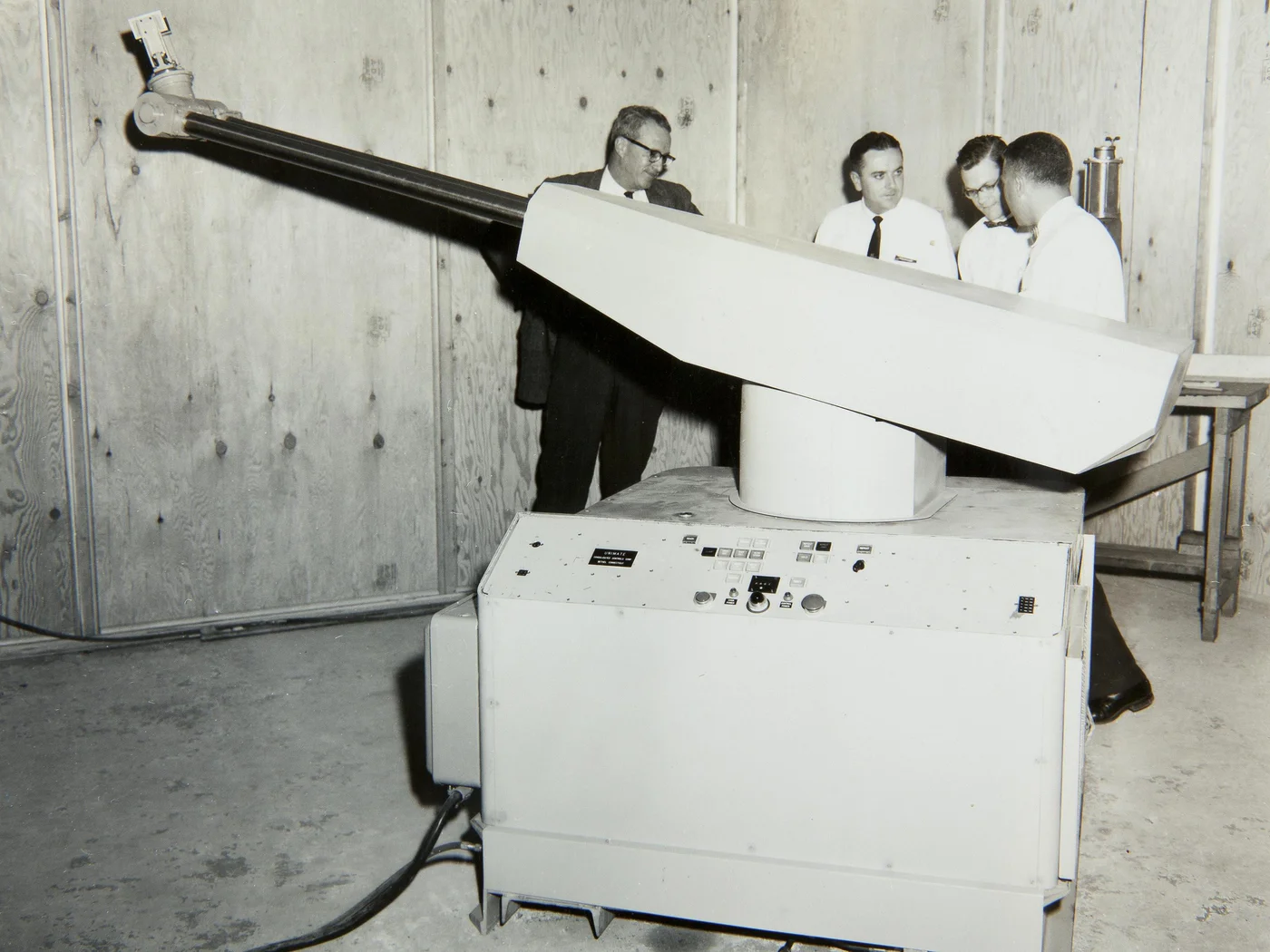

Enter Unimate: The Robot Arrives

In 1961, General Motors installed the first industrial robot, Unimate, at its Ternstedt plant near Detroit. It was a 4,000-pound robotic arm that could perform spot welding without pause or complaint. It didn’t need rest, health insurance, or collective bargaining. Unimate wasn’t just a machine—it was a shift in power.

By the 1980s, GM and Ford had invested millions in automation. Plants filled with robots that moved with inhuman smoothness. The same companies that once relied on human hands now turned to steel limbs and code. For many Detroiters, especially Black workers, this felt like déjà vu: the dream of inclusion, once again made obsolete by the logic of capital. The machines were no longer just on the line. They were the line.

Techno: When the Machines Started Talking Back

And then something strange happened. In the same decades that automation was gutting Detroit’s industrial base, a new sound emerged from its suburbs and city basements. A sound made entirely with machines—but charged with emotion, memory, and political clarity: Techno.

At its core, Detroit techno was an artistic response to the city’s technological trauma. The key players—Juan Atkins, Derrick May, Kevin Saunderson—were the sons of autoworkers, raised on the sounds of collapsing factories and malfunctioning machinery. Atkins famously read Alvin Toffler’s The Third Wave, which described the transition from an industrial to an information-based society. He took that theory and translated it into sound. Atkins once said techno was “like George Clinton and Kraftwerk stuck in an elevator.” “Techno,” for Atkins, “is the music of machines struggling to become human.”

Detroit techno embraced the tools of automation—synthesizers, drum machines, sequencers—but used them to express what the factory floor had suppressed: individuality, syncopation, soul. While the line demanded sameness, techno loops twisted and stuttered. While Unimate moved in predictable cycles, the Roland TR-909 could swing and surprise. It wasn’t nostalgia. It was a reprogramming of the industrial experience. Techno didn’t mourn the machine—it claimed it.

The Emotional Logic of the Robot

Detroit techno was not escapist. It was adaptive. It embraced the machinery that destroyed its industrial landscape and repurposed it as a tool of expression, survival, and identity. Where Ford’s machines demanded repetition, techno’s machines looped into transcendence. Detroit techno wasn’t naive. It knew the robot wasn’t our friend. But it also recognized something deeper: the machine had already reshaped us, emotionally and musically.

The beat of the assembly line became the template for electronic rhythm. The detachment of mechanized labor became the aesthetic of cool minimalism. The loss of bodily autonomy became the architecture of the club—a place where bodies could reclaim rhythm on their own terms.

In this way, Detroit’s robots weren’t just welding parts. They were welding contradictions: between grief and futurism, automation and agency, survival and style.

The Machine Never Left: Contemporary Echoes in Detroit

Detroit never stopped talking to its machines. And the machines never stopped responding. Today, artists, engineers, and musicians across the city are still experimenting with the tensions between automation and expression—channeling the industrial past into aesthetic futures that are often more emotionally and politically nuanced than the techno-utopianism of Silicon Valley.

Underground Resistance and the Political Machine

Founded in the late 1980s, Underground Resistance (UR) emerged from the ashes of a deindustrializing Detroit, a city battered by automation, segregation, and economic abandonment. Rather than retreating into nostalgia or escapism, UR offered a bold sonic counter-offensive. Their motto? “We are the future. We are the resistance. We are UR.” Led by Jeff Mills, “Mad” Mike Banks, and Robert Hood, the collective combined the raw energy of early techno with a radical Black political consciousness drawn from the Black Panther Party, Nation of Islam, and science fiction authors like Octavia Butler.

UR’s releases—often pressed on vinyl with minimal labeling—carried an unmistakable message: music could be a weapon. Tracks like “Sonic Destroyer” and “The Final Frontier” were saturated with industrial textures and mechanical rhythms, but UR always insisted that the machine served the people, not the other way around. As Mills once said, the goal wasn’t just to make people dance—it was to make people think.

UR’s performances and records eschewed personal celebrity, favoring anonymity and symbolism—black ski masks, cryptic messages, coded liner notes. Their label artwork often featured circuitry and dystopian landscapes alongside calls to arms. The “resistance” was more than branding—it was an ideological framework, casting Detroit’s techno underground as a global movement against cultural erasure and corporate control.

Afrofuturism was central to this vision. UR’s work imagined a future where Black identity and machine intelligence were not oppositional but entangled—where the sound of the robot became a language of liberation. In their universe, technology wasn’t neutral. It was political.

Detroit Sound Conservancy: Archiving the Machine’s Echo

If Underground Resistance mapped the future, Detroit Sound Conservancy (DSC) digs deep into the past to keep that future grounded. Founded in 2012, DSC is a nonprofit that archives, preserves, and reactivates Detroit’s rich sonic heritage—not only techno, but jazz, gospel, funk, punk, hip-hop, and blues. Their work makes one thing clear: Detroit’s relationship to sound is inseparable from its relationship to the machine.

One of DSC’s flagship projects is the restoration of the Blue Bird Inn, a storied jazz club that hosted legends like Miles Davis, John Coltrane, and Yusef Lateef during Detroit’s postwar cultural golden age. The Blue Bird fell into disrepair during the city’s long economic decline, but DSC acquired the building in 2018 and began restoring it—not as a museum, but as a community performance space, rehearsal room, and sonic incubator.

DSC also manages an audio archive of rare recordings, radio broadcasts, and oral histories, drawing links between musical communities that are often siloed by genre or generation. Their programming connects early techno pioneers to gospel singers, beatmakers to jazz drummers, showing how the rhythms of Detroit are forged not only in clubs, but in churches, union halls, and neighborhoods.

DSC challenges the notion that Detroit’s sound is a relic of the past. They treat the city’s musical legacy not as a finished chapter but as a living, mechanical system, where old machines hum with new possibility—and where the sounds of resistance are never truly silent.

Interdimensional Transmissions & Movement Festival

Detroit’s Movement Festival is perhaps the most visible expression of the city’s techno lineage. Held annually in Hart Plaza, it draws tens of thousands of attendees and some of the most celebrated names in electronic music. But for many locals, the real magic happens off the grid—in late-night warehouses, underground raves, and parties like No Way Back, hosted by the fiercely independent collective Interdimensional Transmissions (IT).

Founded by BMG (Brendan M. Gillen), IT is known for its radical commitment to sonic exploration. Their events combine analog hardware, modular synths, and hacked drum machines, often in improvised spaces like Detroit warehouses. The aesthetic is lo-fi, intentional, and deeply immersive. It’s less about spectacle than about communion—with each other, with sound, and with the machine.

Their flagship event, No Way Back, rejects flashy headliners or Instagrammable branding. Instead, it’s a 14+ hour journey through raw soundscapes that push both dancers and performers to the edge. The vibe is punk, psychedelic, spiritual. You don’t just attend a No Way Back party—you surrender to it. In a city built by industry and abandoned by it, IT’s events reclaim the machine on their own terms—using wires, feedback, and voltage as a kind of ritual.

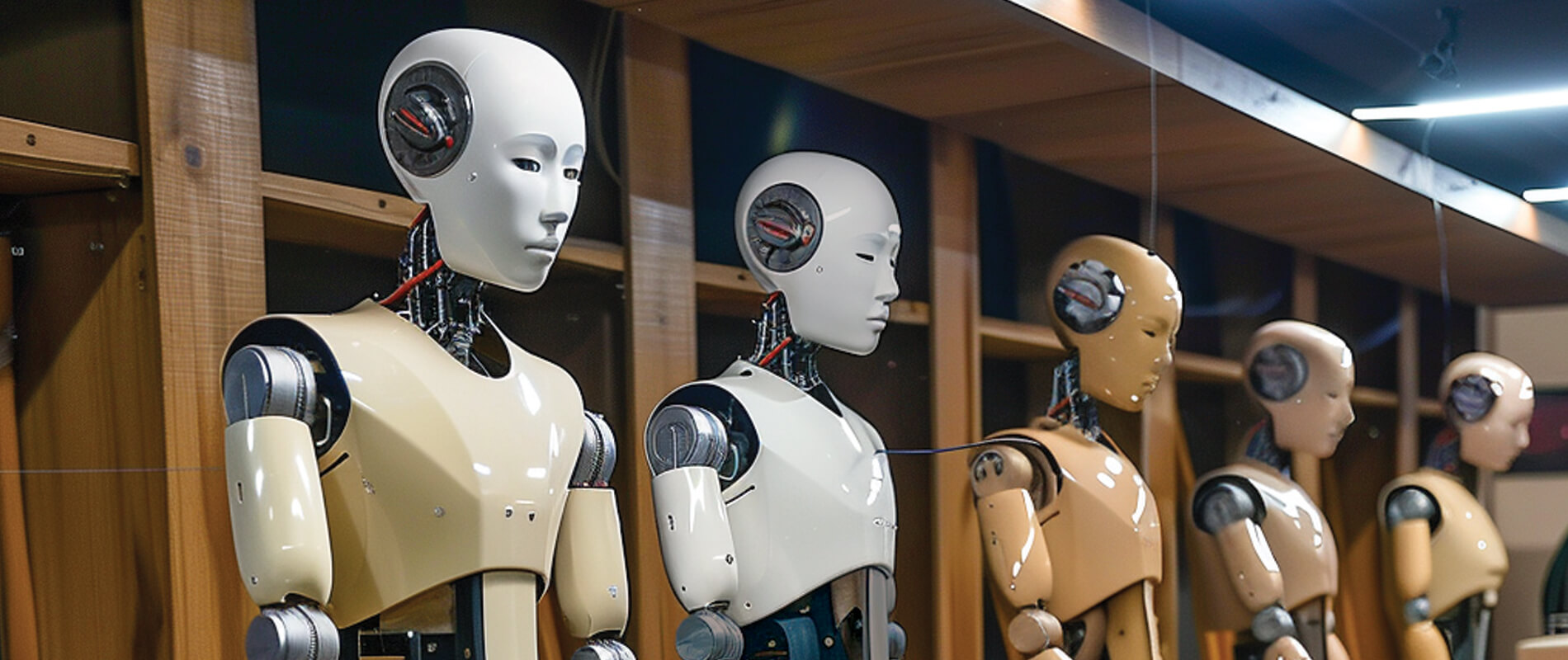

Detroit’s Tech Workforce and the Ghost of Automation

Detroit’s complicated relationship with automation didn’t end with the fall of the factories. In the 2020s, the city is once again being rebuilt by technology—this time through autonomous vehicles, robotics startups, and AI research labs. Ford’s redevelopment of Michigan Central Station into an innovation hub signals this shift. So does the presence of Newlab Detroit, a co-working space for advanced manufacturing and design startups.

But this time, there’s a growing recognition that automation must include people, especially those previously left behind. Programs like Grand Circus and Per Scholas train Detroiters—many of them formerly employed in manufacturing—for careers in coding and tech. Meanwhile, musicians and artists are collaborating with engineers to build tools for adaptive composition, live coding, and machine learning-based improvisation.

Automation is no longer a force of erasure—it’s becoming a language of collaboration. The robot has returned—but in Detroit, it’s being taught to remember what was lost, and to imagine what could still be created.

The Pulse Persists

We live in an age where machines can write music, simulate voices, and remix culture. But if we want to understand what it means to coexist with the machine—creatively, ethically, spiritually—we should begin in Detroit, where the machine is not just a tool. It is a ghost, a memory, a resistance fighter, a beat. Whether it’s encoded in a 12-inch pressing from Underground Resistance or reverberating in a warehouse soundsystem, the pulse of the machine echoes on in Detroit.

But here, the machine doesn’t just compute. It remembers. It resists. It dreams.

by Austin T. Richey, Ph.D.

Digital Media Manager and Storyteller, Detroit Opera