Automatons, Enlightenment, and Early AI

by Austin Richey, Ph.D.

Digital Media Manager and Storyteller, Detroit Opera

Imagine yourself in a Viennese salon, sometime around 1780. Candlelight flickers across parquet floors and gold-leafed mirrors, while the hum of intellectual conversation mingles with the delicate strains of a string quartet. Lace sleeves brush crystal goblets, and powdered wigs nod in agreement—or dissent. Amid the elegance, a new marvel is unveiled: not a new sonata or philosophical treatise, but a machine. An impossibly small child is placed gently on a table. With mechanical grace, the child lifts a pen, dips it in ink, and composes a poem in immaculate calligraphy. This is no sleight of hand. This is L’écrivain, a writing automaton created by the Swiss watchmaker and inventor Pierre Jaquet-Droz.

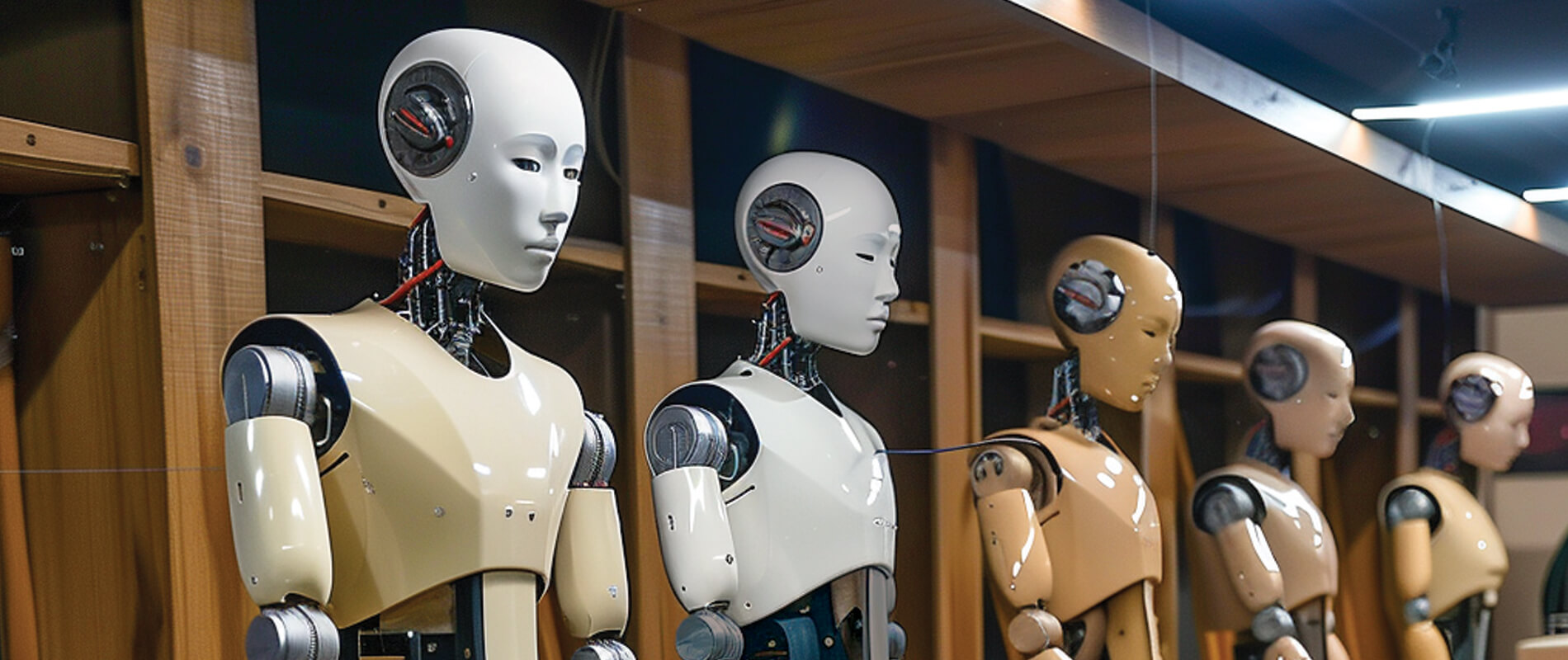

This was the world Mozart inhabited—a world on the brink of the modern, where music, machinery, and metaphysics were tangled in an Enlightenment dream of rational order and infinite possibility. Automatons—exquisitely crafted mechanical beings that mimicked life—were not mere novelties. They were potent symbols of the age’s faith in human reason and its desire to comprehend, replicate, and even improve upon nature itself.

The 18th century witnessed a flourishing of mechanical ingenuity analogous to today’s fascination with artificial intelligence. Figures like Jaquet-Droz and Vaucanson engineered automata that walked, played instruments, and even “breathed,” reflecting a widespread belief that if the world operated like a machine, so too might the body, the mind—and perhaps even the soul.

These machines fascinated not just the aristocracy but also the scientific and philosophical elite. Descartes had already speculated that animals might be automata—biological machines devoid of true consciousness. Enlightenment thinkers such as Julien Offray de La Mettrie took it further, proposing in L’Homme Machine (1747) that man himself was a complex mechanism, sparking debates that echo in today’s discourse on artificial intelligence.

Alongside humanoid automatons, the 18th century was also a golden age for mechanical music. In Mozart’s lifetime, music boxes, barrel organs, and other self-playing devices became increasingly refined. These mechanical inventions could reproduce melodies without a performer—often with delightful, uncanny precision. Clockmakers collaborated with musicians to build timepieces that chimed not just the hour but entire minuets and marches.

Mozart himself was intrigued by these devices. He composed a handful of pieces specifically for mechanical organ or musical clock, including the hauntingly beautiful Andante in F major, K. 616. Written in 1791, the same year as The Magic Flute, the piece was intended for a mechanical organ housed in a clock built for a wax museum.

Far from being a throwaway curiosity, the work is subtle and expressive, raising questions about the role of feeling in mechanically mediated sound. Can a machine move us? Can it play with soul?

Mechanical musical instruments were also common in public squares and aristocratic homes. Barrel organs, for instance, used pinned cylinders to trigger pipes and bellows, producing a full-bodied sound often used to accompany street performances or religious processions. These inventions turned the act of music-making into something automated—predictable, repeatable, and portable. In an era that prized both human genius and mechanical precision, the idea that a machine could “perform” was less threatening than it might seem today. It was thrilling. It proved that art, like nature, could be engineered.

This fascination fed into broader questions about authorship and agency. If a machine could play a sonata, was the expression still Mozart’s—or had it become something else entirely? These were the early murmurs of debates we’re still having in the age of generative AI.

Take the famous Schachtürke, or “Mechanical Turk,” a chess-playing automaton that toured Europe in the 1770s. Dressed in Ottoman robes, it amazed audiences with its ability to beat human players, including Napoleon and Benjamin Franklin. Mozart saw it perform in Vienna in 1769 when he was just 13 years old. He was captivated. Of course, the Turk turned out to be a trick—it hid a human operator inside. But the fascination stuck.

It’s no coincidence that Mozart’s own compositions often evoke mechanical precision—especially in works based on Musikalisches Würfelspiel—a system that allowed anyone to compose music by rolling dice and assembling pre-written bars of music. It was, in a way, algorithmic composition before the age of algorithms.

Today, when we talk about AI in opera—like robotic lovers or algorithmic composers—it’s tempting to see it as a radical departure. But in truth, opera has always been a stage for technological wonder. In Mozart’s day, the line between human and machine was already getting blurry. The Enlightenment gave us not just symphonies, but the earliest sparks of artificial life.

The roots of our fascination with machines that act human—think, move, even love—go all the way back to the salons of Vienna. And Mozart, always tuned into the zeitgeist, gave us music and stories that echo eerily into our own age of algorithms.

Yuval Sharon’s brand new production of Mozart’s Così fan tutte premieres at Detroit Opera on April 5, 2025. For more dates and to buy tickets, click below:

LEARN MORE