September 25, 2025

What Is American Opera, Anyway?

From the earliest stages in colonial America to today’s multimedia productions, the art form of opera has constantly adapted to the cultural moment, often reflecting America’s own contradictions.

Over the past 250 years, opera in America has grown into something wild, complex, and distinctly homegrown. Far from the stereotypes of powdered wigs and operas performed only in Italian, American opera speaks many languages, pulls from countless musical traditions, and has morphed into a medium of fierce storytelling, political critique, and hybrid sound. It thrives because of its porous borders—absorbing the politics, popular music, and spoken vernacular of its time.

Imported but Transformed

American opera didn’t emerge fully formed. It was imported, adapted, and slowly transformed over centuries by waves of immigration, cultural collision, and social upheaval. From its colonial beginnings to its contemporary reinventions, opera in the United States has continually absorbed the musical and political languages of its time. That history, layered with contradiction, aspiration, and exclusion, is crucial to understanding why American opera sounds the way it does today.

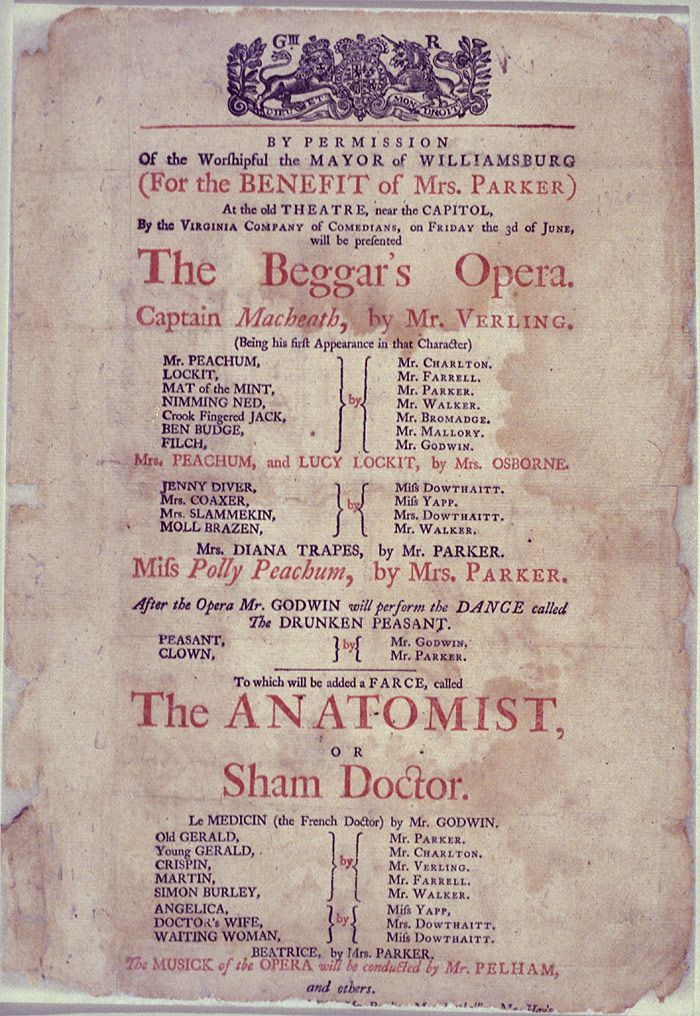

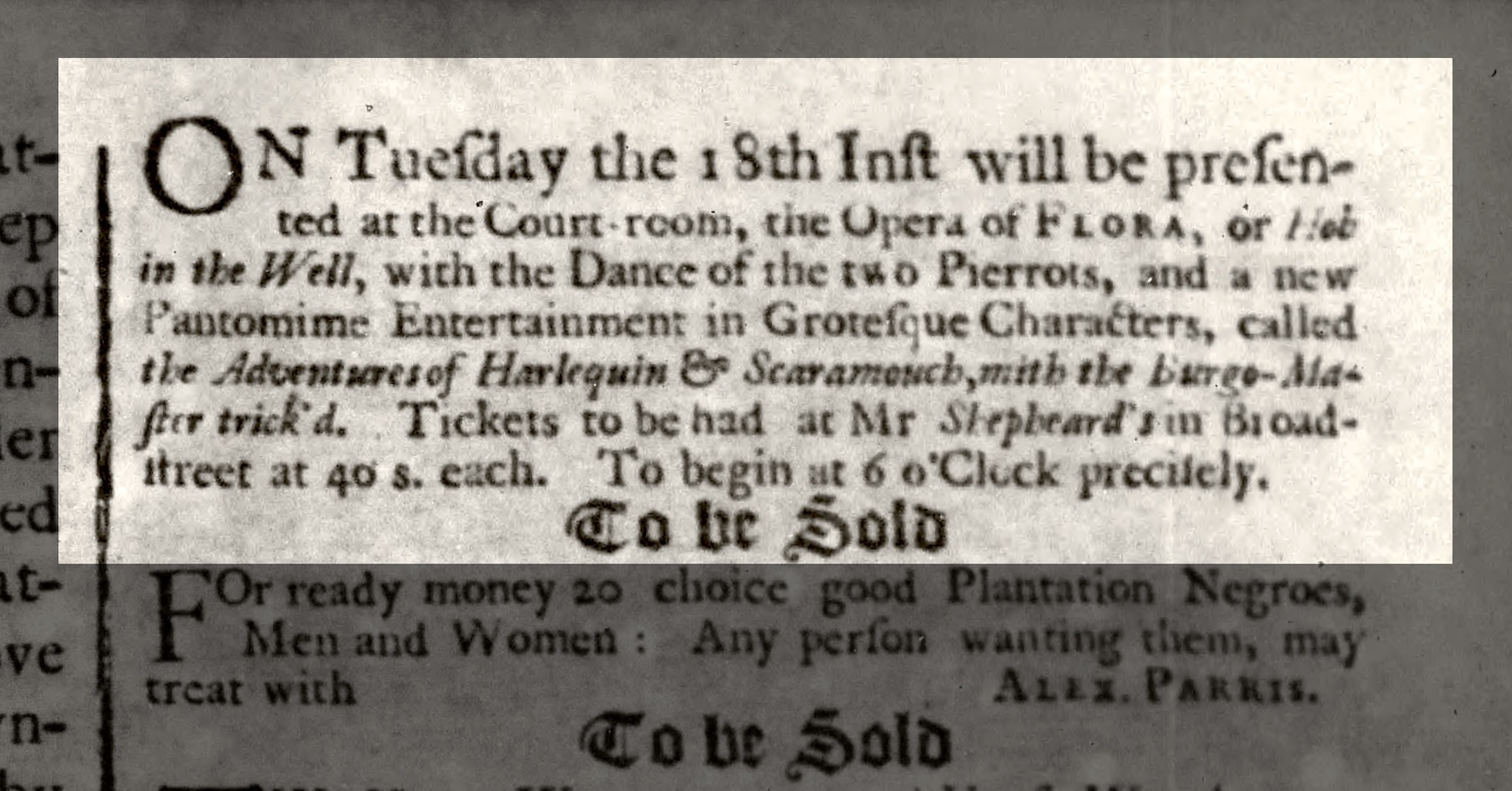

Opera first came to the colonies through European immigrants and traveling companies. By the mid-18th century, cities such as Charleston and New Orleans were hosting opera performances, mostly European imports, translated into English. In 1735, Charleston saw what is believed to be the first opera performance in the American colonies: Flora, or Hob in the Well, a ballad opera of British origin. Such early productions were often staged in taverns and public halls and other makeshift venues, reflecting the colonial elite’s desire to emulate European culture even amid frontier conditions.

These early versions were filtered through colonial ideals and social hierarchies, performed in spaces that often doubled as political meeting halls or ballrooms. In New Orleans, a city shaped by French, Spanish, African, and Caribbean influences, opera became a surprisingly popular pastime across racial and class lines, though segregation and slavery defined who could be in the audience and who could be on stage.

In the early 1800s, New Orleans supported both French and Creole opera houses, with companies performing works by Gluck, Rossini, and Auber. While free people of color could sometimes attend performances or participate in musical life, enslaved individuals were barred. Still, African American musicians—many of them classically trained—played in orchestras or served as music teachers, laying the foundation for the city’s unique blend of European and African musical traditions.

Immigration and Identity

By the 19th century, opera was entrenched in the cultural life of major American cities, carried by the waves of European immigration. Italian touring companies brought bel canto to New York, San Francisco, and Chicago; German-speaking communities championed Wagner and operetta in the Midwest.

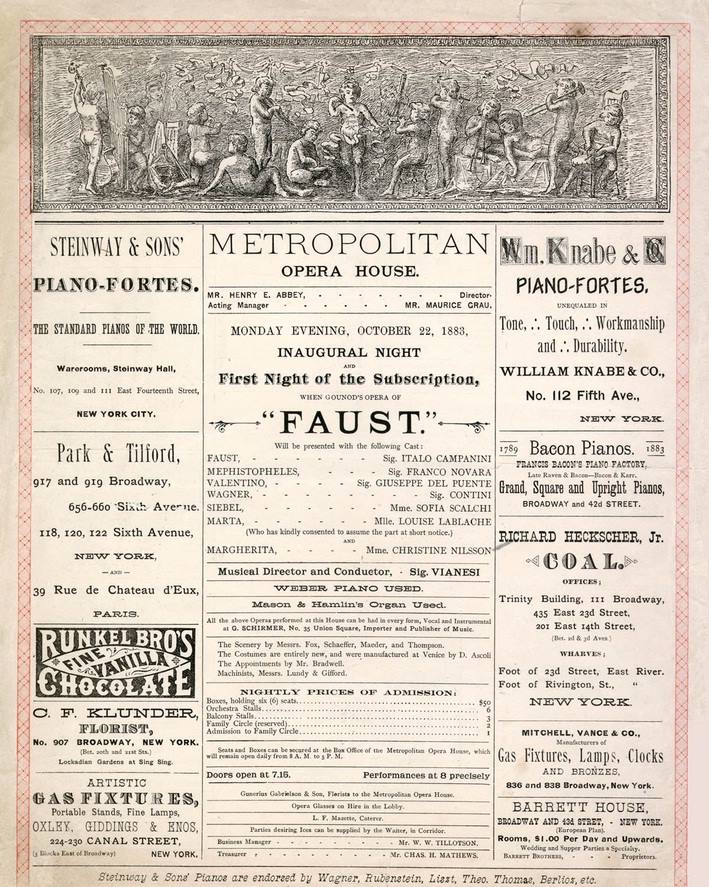

The Metropolitan Opera opened in 1883 with Gounod’s Faust, a symbol of high society’s cultural aspirations. Meanwhile, in cities like Cincinnati, Milwaukee, and St. Louis, immigrant communities formed their own opera companies. In San Francisco, Italian-American audiences supported touring troupes that performed Verdi in Italian, often with local singers in supporting roles. In Philadelphia, the Academy of Music opened in 1857; it is the oldest American opera house still used for its original purpose. German opera houses in places like Milwaukee staged works in the original language, preserving cultural ties while fostering American talent.

These performances often took on an American character—sometimes literally, as works were adapted with new librettos or staged to resonate with local politics and patriotism.

George Gershwin: An “American” Voice Emerges

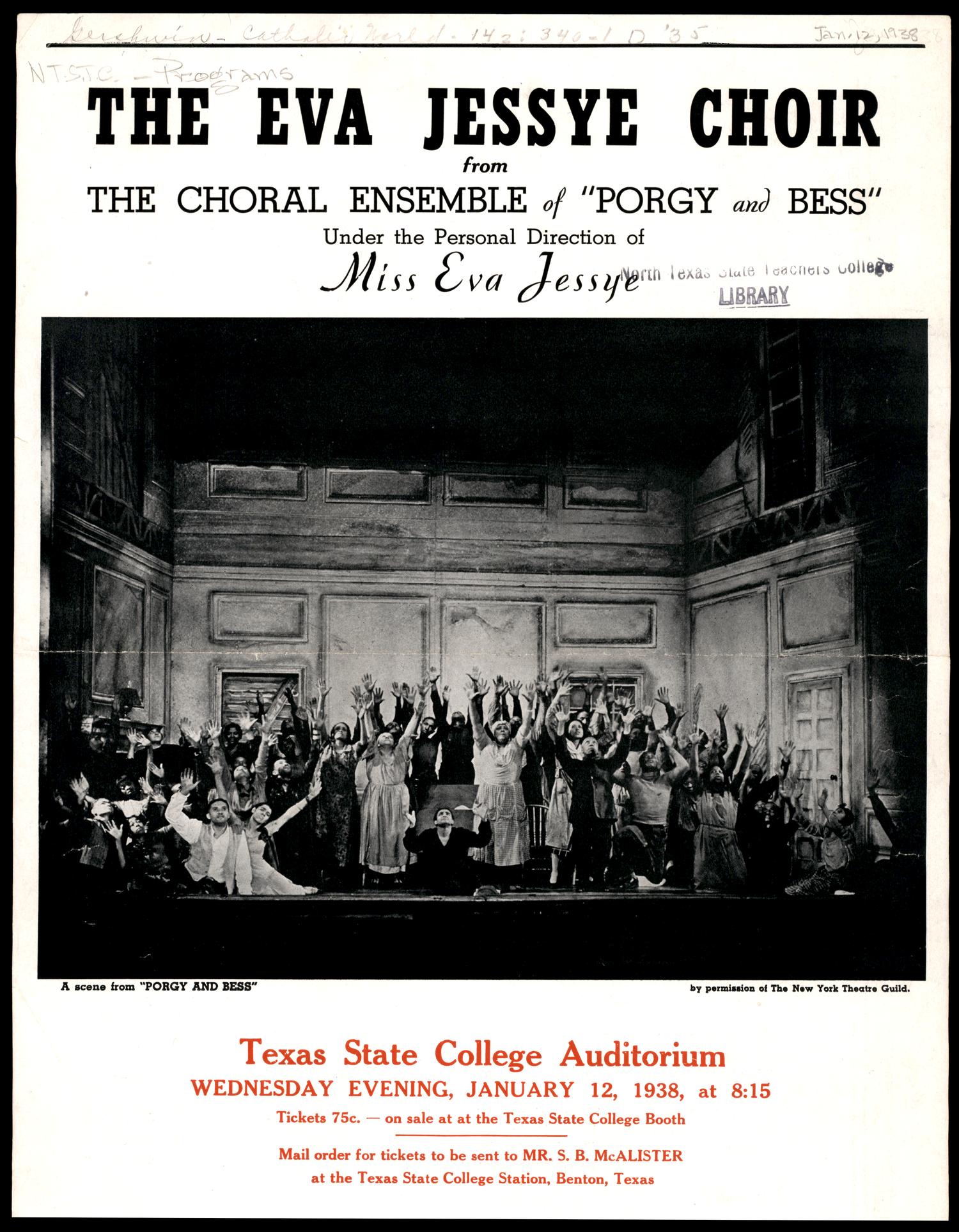

In the 20th century, American composers began putting their own spin on the form. George Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess (1935) was a turning point, blending classical orchestration with jazz, blues, and spirituals. It wasn’t just a new sound—it was a new voice for opera in this country.

Gershwin was already known for bridging classical and popular idioms in works like Rhapsody in Blue and An American in Paris. With Porgy and Bess, he set out to create a “folk opera,” collaborating with Black choral groups like Eva Jessye’s choir and incorporating idiomatic dialect and speech rhythms into the vocal lines. The score moves fluidly between arias, recitatives, and ensemble numbers that borrow from African American traditions while retaining operatic structure.

Gershwin, a Jewish-American composer fascinated with Black musical idioms, sought to create a distinctly American operatic voice that reflected the complexities of Southern life during the Jim Crow era. For Porgy and Bess, Gershwin collaborated with librettist DuBose Heyward (author of the source novel Porgy) and lyricist Ira Gershwin.

Porgy and Bess’s layers of cultural exploration were not without criticism. Heyward’s original novel centered Black life in Charleston’s “Catfish Row,” and his own Southern background lent the libretto a degree of linguistic nuance. However, neither he nor Gershwin was Black, and their interpretation of Black experience—though well-researched—remained filtered through a white lens. The opera’s premiere featured an all-Black cast, but the creative control and institutional power remained in white hands.

Scholar Naomi André has analyzed the opera’s legacy as both groundbreaking and problematic, particularly for how it represents—and at times stereotypes—Black life in the South. In her book Black Opera: History, Power, Engagement, André critiques how Porgy and Bess oscillates between caricature and complexity. While the music affords dignity and depth to the characters of Porgy and Serena, other roles—such as Crown and Sportin’ Life—reinforce harmful stereotypes of hypersexuality or moral deviance. André emphasizes the importance of agency in interpretation and argues for critical engagement rather than dismissal. Early productions of the work often featured all-white orchestras and faced racial casting restrictions, underscoring the deep tensions between artistic ambition and the segregated society in which it was born. Crucially, the Gershwin estate stipulates that Porgy and Bess should be performed by an all-Black cast.

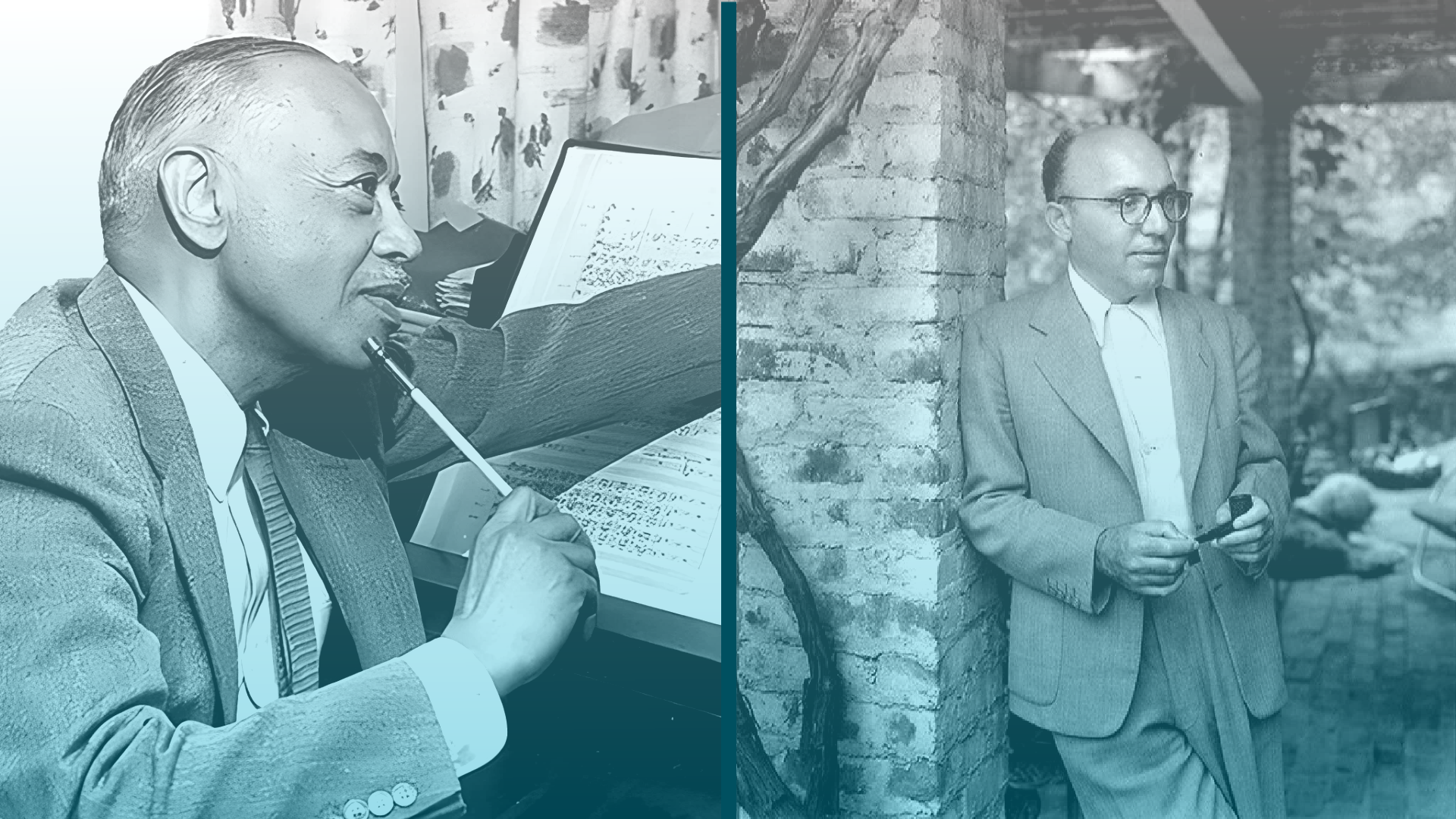

William Grant Still: Opera as a Reflection of America

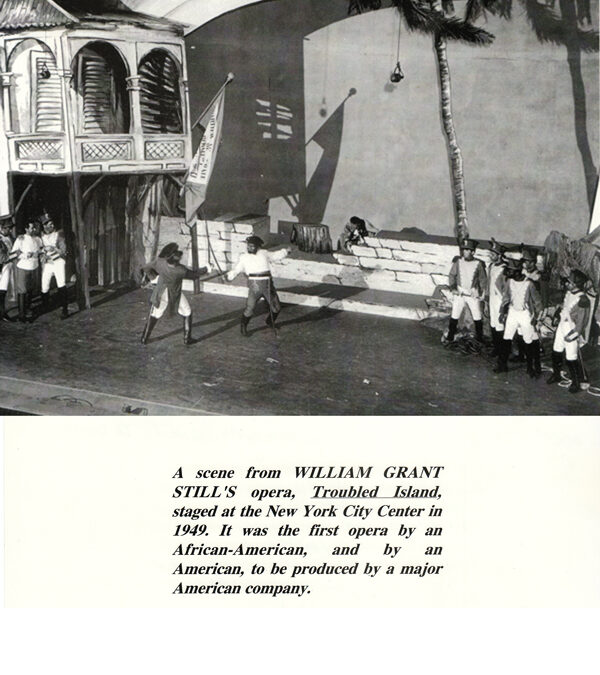

William Grant Still, often called the “Dean of African American Composers,” holds a singular place in the history of American opera. His contributions expanded the boundaries of the form, bringing Black American musical traditions, historical narratives, and cultural perspectives into a genre that had long been dominated by European models. At a time when opera in the United States was still searching for its own identity, Still’s work injected both innovation and representation, positioning him as a crucial figure in the evolution of what we now call American opera.

His most significant operatic achievement, Troubled Island (1949), was the first opera by a Black composer to be performed by a major U.S. company, New York City Opera. With a libretto co-written by poet Langston Hughes and Verna Arvey (Still’s wife), the work dramatized the life of Jean-Jacques Dessalines, the Haitian revolutionary leader who fought against French colonial rule. Still’s music wove together European orchestral traditions with African diasporic rhythms, spiritual-inflected harmonies, and the textures of Black vernacular music. The opera’s chorus, often used as a collective voice of the people, highlighted Still’s belief in opera as a vehicle for communal storytelling.

In choosing the story of Haiti’s independence, Still did more than select a compelling historical subject—he situated opera within the broader struggles of race, freedom, and power. This was radical for mid-20th-century America, where the opera world, like much of society, was segregated and resistant to narratives centering Black figures. The themes of Troubled Island resonated with the era’s global movements toward decolonization, even as critics in the United States often dismissed the work with racially charged language. While audiences responded with enthusiasm, Still’s opera struggled to secure a lasting place in the repertory, exposing the structural barriers that Black composers faced in opera.

In addition to Troubled Island, Still wrote several other operas, including Highway 1, USA (1963), a work that stands out for its intimate focus on working-class Black life. Unlike the grand historical sweep of his earlier opera, Highway 1, USA tells the story of a couple who run a gas station while sacrificing for a younger brother’s education. With its lyrical writing, jazz-inflected idioms, and themes of family and responsibility, the opera embodies Still’s vision that opera could reflect the lived realities of everyday Americans, not just mythic, heroic, or aristocratic figures. In this way, Still helped pave the way for later generations of composers who used opera to grapple with contemporary social issues.

Still’s operatic legacy lies not only in the works themselves but also in what they represented for the identity of American opera. By fusing classical form with blues, jazz, and spirituals, he created a sound world that was distinctly American. By foregrounding Black stories and characters, he challenged the opera establishment to reconsider whose voices and histories belonged on stage. His contributions resonate alongside those of later composers like Anthony Davis and Terence Blanchard, who have continued the project of making opera a space for political, racial, and cultural reckoning.

Ultimately, William Grant Still’s work reminds us that American opera is defined not by imitation of European traditions but by transformation—by absorbing the voices, struggles, and dreams of the many communities that make up the nation. In placing Black narratives at the center of the operatic stage, Still expanded the canon and redefined what opera could be in America. His achievements, too often overlooked, stand as a cornerstone in the ongoing story of opera’s evolution on this side of the Atlantic.

John Cage: American Attitudes in Opera

John Cage is rarely the first name that comes to mind when we think of American opera, yet his work fundamentally redefined what the form could mean in the late 20th century. Where William Grant Still and George Gershwin embedded vernacular idioms into operatic tradition, Cage broke down the very assumptions of operatic storytelling—plot, character, linear time—and replaced them with open-ended experiments in sound, chance, and perception. His operas are less about grand narrative and more about the conditions of listening itself. In doing so, Cage opened opera to new possibilities, situating it within the wider avant-garde and aligning it with distinctly American values of pluralism, experimentation, and critique.

Among his major stage works, Europeras (1987–91) stands as a notorious provocation: five sprawling operas made entirely of fragments from the European operatic canon, cut up, randomized, and performed according to Cage’s chance procedures.

The title itself is a mashup of “Europe” and “opera,” and the work functions as both homage and dismantling. Cage once remarked that he was “giving Europe back its operas,” liberating them from the weight of tradition and allowing their pieces to collide in ways that defy historical or stylistic coherence. Singers, arias, staging, and orchestration operate independently, often comically or absurdly, creating an opera without hierarchy, where everything happens at once. In this way, Cage turned the opera house into a site of radical simultaneity, undermining centuries of narrative authority and re-centering the act of listening itself.

Cage’s engagement with opera was not always parody. Apartment House 1776 (1976), created for the U.S. Bicentennial, is one of his most ambitious and subtle contributions to American opera. Commissioned to mark 200 years of national history, the work explores the cultural multiplicity of 18th-century America through overlapping soundscapes rather than linear story. Cage drew on four musical traditions present in the American colonies: Native American songs, Black spirituals, Sephardic Jewish melodies, and Protestant hymnody. Instead of weaving them into a single unified voice, he allowed each tradition to remain distinct, performed simultaneously in independent layers. The result is not a melting pot but a sonic collage, acknowledging the coexistence—and tensions—of diverse cultures at America’s founding.

In Apartment House 1776, Cage used his signature chance operations to determine musical structure, but the performers’ autonomy was central. Each singer or instrumentalist carried their tradition independently, and the audience experienced the work as an overlapping mosaic of sound. What emerges is not harmony but coexistence—sometimes beautiful, sometimes dissonant. In this way, Cage anticipated later debates about multiculturalism and national identity. He refused to smooth over difference into a single narrative of “America,” instead presenting history as a cacophonous simultaneity, a radical gesture for a Bicentennial celebration otherwise dominated by patriotic pageantry.

Cage’s operas resist the expectations of character, plot, and climax, but they remain deeply theatrical. They ask audiences to sit with contradiction, silence, and the unexpected. In doing so, they also reflect America’s contradictions: its competing voices, its uneasy relationship with its own history, and its constant reinvention of cultural form. Where Still used opera to dramatize liberation and Gershwin to fuse idioms, Cage used it to dismantle hierarchy and open the form to chance, multiplicity, and doubt.

The legacy of Cage’s operatic work, and especially Apartment House 1776, lies in this radical reorientation. He expanded the idea of what could count as opera in America—not by adding new stories to old forms, but by questioning the very structures of operatic storytelling. In his hands, opera became less about fixed meaning and more about the conditions under which meaning might emerge. That move, unsettling as it was, has had a lasting impact on experimental opera and performance, shaping generations of composers and directors who continue to see the opera house as a space not just for narrative but for questioning the nature of art, sound, and society itself.

What Makes It “American”?

American opera is often:

• In English, though not exclusively.

• About American themes—race, politics, labor, identity, myth.

• Musically diverse, borrowing from folk, jazz, minimalism, hip-hop, and more.

By the mid-20th century, a new generation of American composers was no longer content to simply borrow from European models. They began reshaping opera’s foundations, embedding the form with local dialects, political urgency, and vernacular music. These artists used opera to confront the complexities of American life—its promises and its failures. What followed was a creative flourishing that broke open the canon and brought voices long pushed to the margins into the center.

These works interrogate the American experience from different vantage points—past, present, mythic, personal. Together, they show how opera in the U.S. is not defined by any one sound or story, but by a restless commitment to reimagining what the form can be, and who it can speak for. Consider John Adams’s Nixon in China (1987). Written during the Reagan years—a decade dominated by image-making and Cold War diplomacy—Adams was interested in mythologizing contemporary political events, treating Nixon’s 1972 visit to China as if it were a Wagnerian epic.

Drawing on real-life figures like Richard Nixon, Henry Kissinger, Mao Zedong, and Madame Mao, Adams built a libretto around actual transcripts and press releases, elevating banal political language into heightened lyrical drama. The opera’s opening scene, where Nixon descends from Air Force One to meet Zhou Enlai, becomes a moment of quasi-religious ceremony, complete with heroic brass and choral grandeur—casting a routine diplomatic photo-op as if it were a scene from Parsifal.

His minimalist techniques—repetition, textural layering—offered a new language for political opera, one that emphasized ritual over spectacle. Instead of grand arias or emotional outbursts, Adams focuses on the hypnotic rhythm of bureaucratic speech. In “News Has a Kind of Mystery,” Nixon muses over his public image and media control, with looping musical motifs that echo the sound of machinery and officialdom. Madame Mao’s Act II aria, “I Am the Wife of Mao Tse-Tung,” meanwhile, bursts out of the minimalist palette with piercing coloratura passages and percussive force, disrupting the hypnotic surface and signaling the volatility beneath political theater. Working with director Peter Sellars and librettist Alice Goodman, Adams created a work that feels at once documentary and dreamlike—a hallmark of postmodern American opera, reflecting both media saturation and the surreal theater of politics.

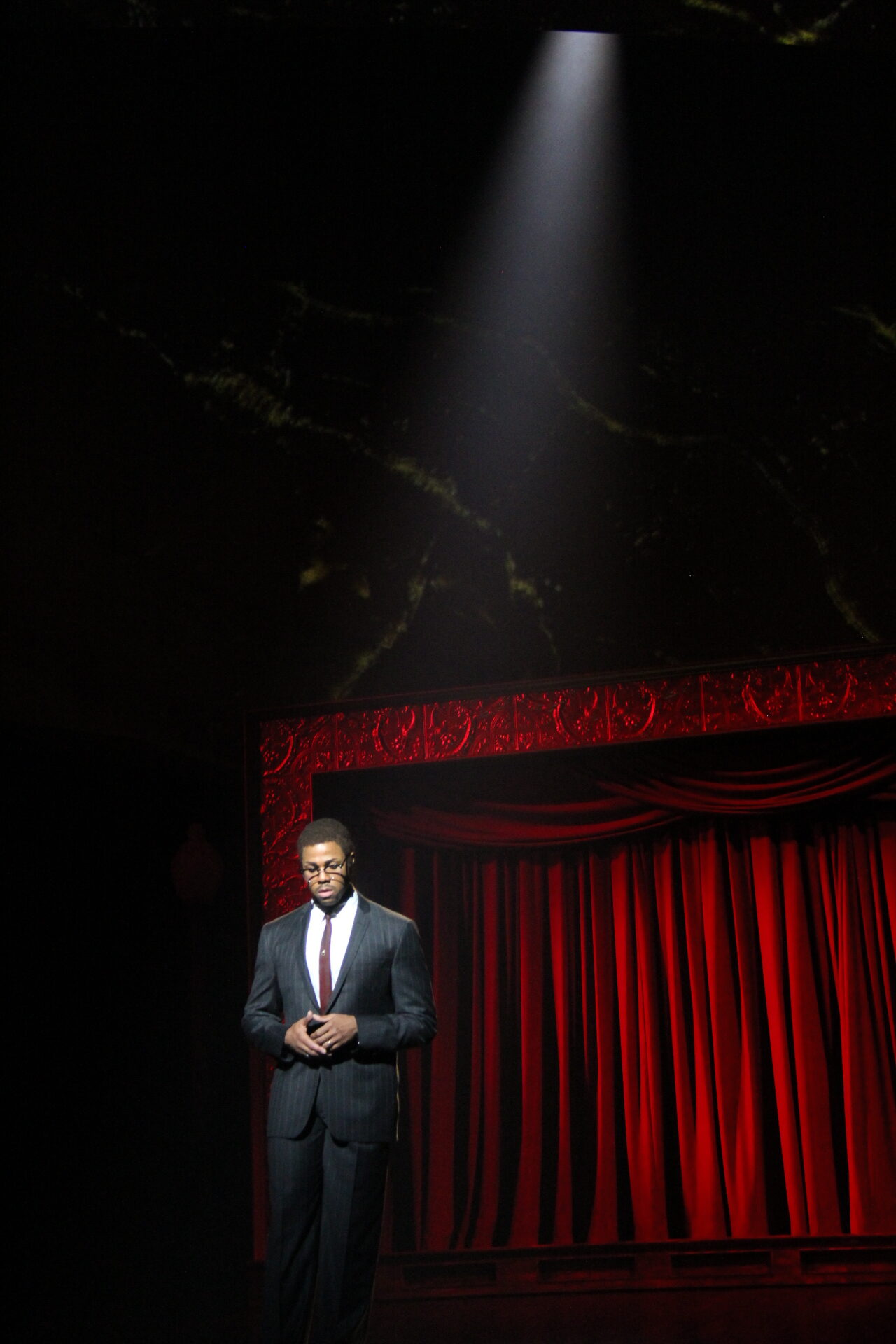

Then there’s Terence Blanchard’s Fire Shut Up in My Bones (2019), which sets Charles M. Blow’s memoir to music with jazz-inflected orchestrations and gospel-tinged arias. The opera opens with a haunting refrain sung by a lone child soprano—Blow’s younger self—establishing a tone of vulnerability and inner conflict. Musical themes from Black church traditions recur throughout, especially in the character of Destiny, a mystical figure who guides Blow’s journey. The Act II fraternity step scene pulses with syncopation and percussive energy, echoing historically Black college step shows and layering contemporary Black identity into the musical fabric.

Written in an era of heightened conversations around race, sexuality, and identity, the opera addresses trauma, resilience, and self-discovery. Blanchard, a jazz trumpeter and film composer known for his decades-long collaboration with Spike Lee, brought a cinematic sensibility and deep familiarity with Black musical traditions into the opera house. The Metropolitan Opera’s 2021 staging of Fire Shut Up in My Bones marked the first time in its 138-year history that a work by a Black composer appeared on its stage—an overdue milestone that resonated in the wake of nationwide calls for racial justice.

The production, directed by James Robinson and co-directed/choreographed by Camille A. Brown, was notable not only for its cast of majority Black performers—including baritone Will Liverman and soprano Angel Blue—but also for Brown’s choreography, which filled the stage with vernacular dance. In one particularly powerful moment, the character of Charles confronts his abusive past while surrounded by dancers embodying inner turmoil, blurring the lines between memory and embodiment, trauma and performance.

Missy Mazzoli’s Proving Up (2018) uses surrealism and chamber instrumentation to explore the American frontier myth. The opera follows a Nebraska homesteading family in the 1870s desperate to fulfill the literal requirements of the Homestead Act—most absurdly, a glass window, which becomes a fragile symbol of legitimacy and hope. With a libretto by Royce Vavrek, the story is based on a short story by Karen Russell, and leans into dream logic, ghostly apparitions, and disintegrating time. Mazzoli’s music is sparse but deeply textured—featuring eerie harmonicas, string glissandi, and disembodied vocal echoes. One of the opera’s most striking moments comes when the child protagonist, Miles, rides alone across the plains, encountering spectral visions that blur the line between hallucination and historical trauma.

Created in the shadow of 21st-century economic inequality, Proving Up interrogates the dream of land ownership as a birthright. Inspired by Laura Ingalls Wilder’s vision of pioneer life and filtered through macabre ghost stories, Mazzoli—one of the most prominent women in contemporary opera—crafted a haunting meditation on entitlement, failure, and the collapse of ideals under capitalism.

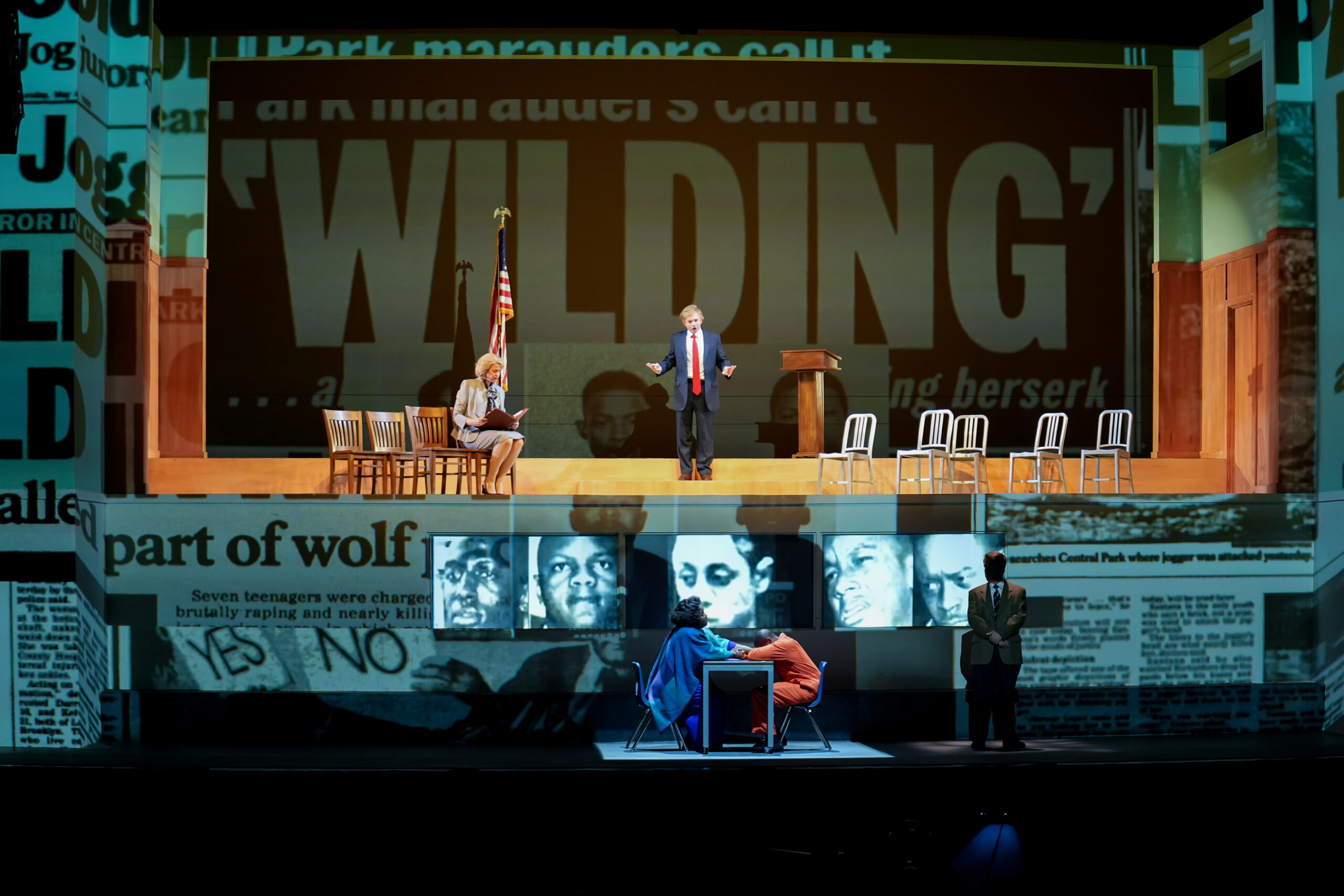

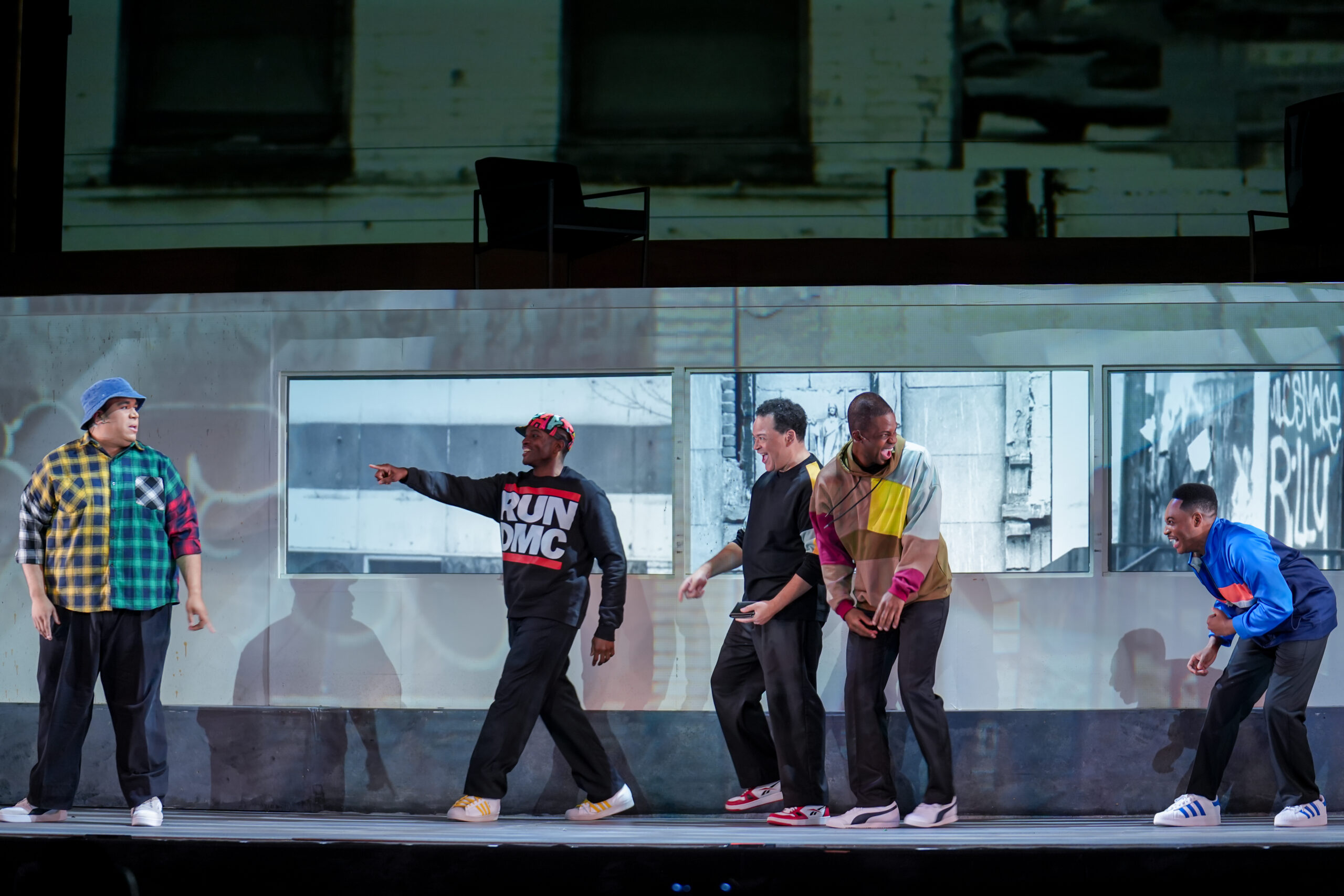

Anthony Davis’s The Central Park Five (2019) revisits the wrongful conviction of five Black and Latino teenagers in late-1980s New York. The opera presents each of the Five—Kevin Richardson, Antron McCray, Raymond Santana, Korey Wise, and Yusef Salaam—as individual voices in a fragmented social chorus, often forced into unison by the pressures of police interrogation. The score draws from Davis’s background in free jazz and atonal modernism, using dissonant brass and sharp rhythmic pulses to evoke chaos, injustice, and rage. The character of the “Masque”—a shape-shifting figure representing white supremacy and media bias—narrates and manipulates events with biting sarcasm, serving as both a Greek chorus and a stand-in for institutions. In the trial scene, the boys’ voices are overpowered by waves of ensemble sound, illustrating how their individual truths were drowned out by public hysteria.

Written during a period of renewed scrutiny of American policing and mass incarceration, Davis uses angular melodies, spoken word, and harmonic tension to critique systemic racism and media manipulation. Davis, a veteran of the Black avant-garde jazz movement whose compositions draw on jazz and other elements from outside of the traditional classical idiom, had already tackled monumental political biography in X: The Life and Times of Malcolm X (1986). For him, opera serves as a vehicle for narrative justice—reclaiming stories misrepresented by dominant media.

So What Is It, Really?

American opera isn’t one thing. It’s a layered, multilingual, multi-stylistic tradition that keeps expanding. It’s less about defining a genre than about asking questions:

Who gets to tell the story?

What is sacred?

What’s worth disrupting?

From colonial stages to Black avant-garde collectives, from midcentury modernism to feminist punk operas, the form has been a mirror—sometimes flattering, often uncomfortably honest—of the country’s evolving identity.

Over time, American opera has been shaped by its inherited structures and the artists determined to bend or break them. It has been used to mythologize political events, like Nixon’s visit to China; to interrogate national traumas, like the wrongful imprisonment of the Central Park Five; and to reframe the frontier, as in the haunting surrealism of Proving Up. Composers William Grant Still, Terence Blanchard, and Anthony Davis have used the form to reckon with race, representation, and American power—often pushing against an opera industry slow to make space for Black narratives. Meanwhile, artists like Missy Mazzoli and John Adams have reimagined what opera can sound like, weaving in electronics, folk idioms, and experimental theatrical structures to confront systems like capitalism, patriarchy, and power.

Opera in America is alive because it’s still searching for its own voice, and finding new ones all the time. Whether channeling jazz, gospel, minimalism, punk, or spirituals, American operas do not merely reflect the nation—they challenge its myths, complicate its history, and expand its imaginative potential.

by Austin Richey, Ph.D.

Digital Media Manager and Storyteller, Detroit Opera